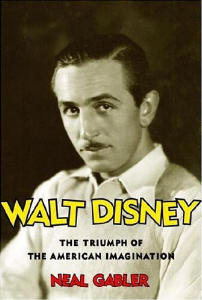

Rhett Wickham: A review of Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination

Page 1 of 2

Seriously Walt

A Forrest of Research Blocks

Any New Light From Being

Shed on the Life of Walt Disney

Rhett Wickham Reviews Neal Gabler's

Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination

According to the press releases, award winning author Neal Gabler was given one directive from Walt Disney publicist Howard Green after Roy Disney gave the author carte blanche in his quest to write the definitive Disney biography – write a “serious�? book. Sadly, Gabler has done just that.

Neal Gabler has previously proven himself an accomplished and solid biographer and historian. His two other works, Winchell: Gossip, Power and the Culture of Celebrity and An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood, are both important and insightful books, particularly the exhaustively researched and entertaining Winchell biography. With these writings, Gabler would seem to be the ideal candidate to take on the quest of finding the real hidden Mickey deep in the psyche of Walt Disney. But for all his academic due diligence, including unprecedented access to the Disney Archives (which the author refers to in his publisher's press releases as being “as impregnable as the old Soviet Kremlin�?) Gabler stumbles head-long down the path to truth and ends up with a severely bruised view of Walt that feels oddly scraped and scarred by the contemporary corporate culture of Disney.

Burdened by Eisner-era financial myopia, Gabler is convinced that there must be something darker about the decidedly American ambition of his subject, and writes in a tone that feels suspicious of the optimistic spirit of Walt, sometimes snobbishly contemptuous of his Midwestern ideals, and determined to bust the myth of the simple man. How accurate a biography can someone write if they approach their subject with such overwhelming suspicion? Once you've waded through the 600 plus pages of text (accompanied by another 200 pages of appendices and notes) you get the feeling that the book's title, Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination is a poorly disguised way of insisting that Walt Disney was determined to rule popular culture and the collective conscience with his own way of thinking. Mark Eliot's patently absurd Walt Disney: Hollywood's Dark Prince (graciously debunked in Gabler's book) was bad enough, but did we really need Walt reinvented as Machiavelli of the plains? This otherwise impressively annotated and occasionally thoughtful book is littered with cynical conclusions that weigh it down with an unnecessarily overly-complicated post-modern perspective of a restlessly tortured creative genius attempting to de-throne God himself. Gabler assigns Walt a ridiculous birthright: escape the dreary and barren streets of Kansas City and Chicago, go forth, and conquer the nation – nay, the world! In writing about Walt's admission to columnist and critic Jimmy Starr that too much time went into the making of the (then) financially unsuccessful Bambi, Gabler concludes:

It was a painful admission. Walt Disney had lived to spend time on his features, lived to create a fully realized universe that testified to his power and provided his escape.

Good heavens, cue the thunder and turn on the wind machine. While Gabler's subtler supposition is not disinteresting, nor necessarily unworthy of debate, he is so consistently heavy-handed that it is sometimes comical. At times, his definition of what Walt was seeking to "escape" shifts ever so slightly, according to what Gabler is attempting to argue. Gabler also insists on repeatedly emphasizing in the press his amazement that the founder of such a powerful entertainment empire could have ever allowed himself to be so precariously and constantly poised near bankruptcy for most of his life. This is emphasized throughout the book, and it begs the question of whether Walt was truly successful, and thus truly happy, and draws an unmistakable and unfortunate link between the two. At the same time Gabler frequently glosses over the contributions of the pioneering artists who helped define the Disney brand and sees them merely as contributors to his quest to unravel Walt, oddly ignoring the opportunity to better understand what it was that Walt knew about capitalizing off of the talent of other equally (or even arguably more) talented artists who devoted themselves to his vision. Of course Gabler is at a distinct disadvantage that he willingly acknowledges in the book's introduction – the fact that most of these voices are now silent, having died down to but a handful of women and men who knew Walt personally (or at least as personally as anyone could.) Sadly, Gabler never once gives any serious analysis to what Walt saw in these artists, what he willingly took from them, or the larger impact of co-opting someone else's genius in service to his own vision. The meat of the prose that has been packed onto what is otherwise a book with very, very good bones, is from the wrong animal entirely. Gabler is analyzing a part of Walt that quite possibly never existed, except in the minds of information-age pundits like him.

Gabler the reporter of facts is without peer, and when he sticks to the facts and just the facts, he crafts solid and admirable prose, never boring us as he guides us through the history, but he doesn't give us anything truly interesting to ponder. Ultimately, Gabler the biographer speculates too much about the wrong things. This makes his darker conclusions seem gossipy, and the author slips into his past life as a film critic, making careless and, frankly, overwrought statements. Mired somewhere between being a serious writer and cable television commentator, Gabler ultimately fails to disguise basic spin behind a preponderance of pages. It's a terrible waste of otherwise solid writing talent on a terrific subject. Gabler is not alone in his failed ambition, however. There are other very bright and serious commentators on the contemporary Disney culture and corporate matters who insist on spinning the most absurd drama where none exists. It is not surprising that the greatest praise for the book has come from just such sources – as they compliment each other. They leave any serious Disney devotee dehydrated thanks to an endless supply of half-empty glasses.