Jim on Film

Page 2 of 3

(c) Disney

Tuck Everlasting

Whereas most stories with strong themes leave the viewer with a new outlook on

life, Tuck Everlasting was one of those films that made me leave the

theater discussing (a rare distinction shared with few films, such as Evita

and The Passion of the Christ). The Tuck family is everlasting because

they have a fountain of youth, water at the base of a tree that allows them to

live forever. Finding comfort in their freedom, young Winnie Foster finds

herself happily imprisoned with the family, falling for their younger son Jesse.

As she learns the secret to the special life they lead, Winnie finds herself

confronted with the option of drinking from the fountain.

In a dialogue between the elder Tuck and Winnie, the film challenges us to live a full life in the time we have, a wise urging since there is no fountain of youth for us to consider. But more than this message, the film causes us to really question our own lives, to see what we would do in a similar situation. Deceptively based on a children’s novel, Tuck Everlasting is not a film that wants us to believe something; it’s a film that wants us to decide for ourselves.

(c) Disney

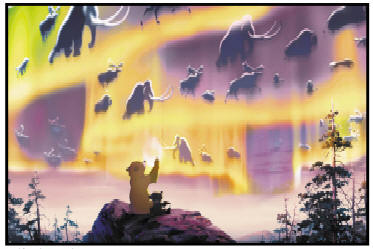

Brother Bear

By the time Brother Bear hit theaters, critics and audiences were used to

more traditionally expected Disney themes, such as follow your dreams in

Atlantis: The Lost Empire, look beyond appearances in Beauty and the

Beast, or the pro-environmentalism ideas thought to be in Pocahontas

and Tarzan. Because of this, they were quick to discard Brother Bear

as a film against hunting, a piece of environmentalist propaganda. Phil Collins’

great song Look Through My Eyes, however, sums up the theme of the film

in a much more concise and accurate manner.

The problem was that people’s minds went on automatic pilot and never stopped to consider what the film was really saying, which suggests why the ending was cryptic or confusing to some critics (including Leonard Maltin’s Hot Ticket co-host Joyce Kulhawik). Because I tend to be a person who is too empathetic anyway, this theme was not one that particularly resonated with me; however, I was deeply appreciative of the literary nature in which the theme was explored. I saw Brother Bear five times in the theater, and each time, I found myself coming to a better understanding and appreciation of what the filmmakers were doing.

In Brother Bear, a young man kills a bear in retaliation for his brother’s death as a result of a bear attack. To better understand the perspective of the bear, Kenai, the young man, is transformed into a bear. Confused and bitter, Kenai sets off to find out how to change back into a human and along the way encounters Koda, a cub who has lost his mother. As the two journey together, Kenai begins to understand the perspective of the bears. He realizes that the bear attacked to save her cub, something he finds himself doing in a moment of panic. Once he’s learned this valuable lesson, Kenai returns to his human form; however, after having had a chance to look through another’s eyes, Kenai realizes that he needs to suppress his own desire for a human life in order to help another, little Koda. Never once is it shown that Kenai’s slaying of the bear is wrong in itself; it’s wrong because he did it for the wrong reasons, without looking through the bear’s eyes.