“Hey, it’s Animated Features night at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences!” With these words Academy Governor Bill Kroyer kicked off the tenth annual presentation for Animated Feature nominees at the AMPAS Samuel Goldwyn Theater in Beverly Hills. Kroyer noted that the award had been established 17 years ago. He also noted that three types of animation were represented in this year’s nominees: CG (The Boss Baby, Coco and Ferdinand the Bull), 2D (The Breadwinner), and an unusual entry, the oil painted Loving Vincent.

The panel for Animated Features (c. AMPAS)

Traditionally the recipients of the previous year’s award host the evening. As Zootopia was that film, it was expected that the three winners of the award would be present. Unfortunately, Rich Moore and Clark Spencer were down with the flu, so it was up to Byron Howard to handle hosting chores alone.

“Solo, my friends!” cried Howard as he took the stage. He slyly noted that Moore and Spencer had been working on Wreck-It Ralph 2: Ralph Wrecks the Internet and had acquired… a virus. (Get it?) On a more personal note, he added, “I love this evening almost more than any other evening during Oscar season.”

THE BOSS BABY

The first film up for discussion was The Boss Baby. Following a clip depicting the first encounter of boss baby, Alec Baldwin, with his new older brother, Tom McGrath and Ramsey Naito took the stage. Byron’s first question came right to the point. “I thought I knew where babies came from… how did this idea originate?” The story was derived from a book that focused on how babies became the “boss” of their homes. They decided to take the baby from Mega Mind and the boss from 30 Rock and combine them into one character. The designers were encouraged to use 2D techniques in development; the work of Bob Clampett was a primary inspiration.

Howard asked if Baldwin’s appearance in Glengarry Glen Ross served as an inspiration for the management side of Baby World. McGrath cited his work with Baldwin on Madagascar. But, he added, the real linchpin of the movie was the “kid,” the older brother, played by Miles Bakshi, the grandson of animator Ralph Bakshi. Because of the extended production schedule, he started playing the role at age 10 and did his last recording sessions at age 15. Six years was the total schedule for the film. During that time, the producers pointed out, Alec Baldwin started a new family and had three kids—so he had a lot of inspiration from which to draw.

Howard asked how much the script evolved over those six years. McGrath stated that the script was developed early and just got better. Naito said the story was so solid that it was just a matter of refining and adding better jokes.

Howard then brought up the comedy aspect of the film, saying that while it was sold as that, it was really a film about the relationship between the two brothers. McGrath said this was something the producers added. Rather than simply showing a new baby taking over a family, they made it into more of a sibling rivalry story. “Laughter is the doorway to the heart,” he said, and comedy could disguise an underlying story about the two brothers. Anyone with a brother or sister would understand this. Howard asked if McGrath had a big brother or little brother. “I am the boss baby,” he proudly replied. Naito recalled when McGrath’s brother was first shown the film. There were tears, and hugs. McGrath added, “And then we fought!” For her part, Naito has three sons, so she lived the story.

Howard next asked if they spent much time studying babies while making the film. McGrath chuckled as he said that they studied puppies. They even had a “puppy day.” But they did, of course, study a lot of baby behavior, especially in the abundant material available on YouTube. Their biggest technical challenge was “baby jiggle.”

Howard next touched on the use of the Beatles song “Blackbird” as a story point. Why that particular song, and was it difficult to get the rights to use it? It turns out that an original lullaby was offered for the soundtrack, but the producers and many animators sang “Blackbird” to their babies. And the rights were rather easy to secure.

A final question dealt with foreign versions of the film. The Boss Baby was translated into 60 languages. Jokes had to be tailored for each culture. And, according to the filmmakers, there was already an Alec Baldwin sound alike available in virtually every one, due to years of dubbing episodes of 30 Rock.

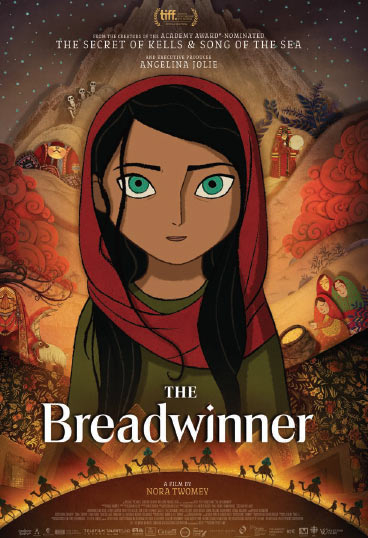

THE BREADWINNER

The next film discussed was The Breadwinner. This traditionally animated feature tells the story of a young woman passing as a boy in the Taliban era in Afghanistan. When her father is imprisoned she must venture out to earn money to support her family. Along the way she meets another girl who is also passing as a boy. Howard complimented filmmakers Nora Twomey and Anthony Leo on the emotion expressed in the clip, and how much anxiety he felt for the two young women. Leo cited the source material, the young adult novel written by Deborah Ellis. He first encountered it being read by a nine-year-old girl, and ended up reading it after dinner each night. It was originally optioned as a live action film. But as the script was developed, they decided that animation would make it more accessible to its young audience. Cartoon Saloon seemed a natural fit, as they had produced The Secret of Kells. Twomey read The Breadwinner in one sitting and decided take on the project.

Howard asked about the shift from the fairy-tale world of Kells to the gritty reality of The Breadwinner. Twomey felt that the importance of The Breadwinner made it imperative. So much was happening in the world—to the Afghan people, different religions, and different ethnicities.

Casting was the next subject at hand. Producer Angelina Jolie took an active hand, insisting that they cast Afghan actors in all the roles. In the end the producers did have to go to several countries due to difficulties in the region.

While The Breadwinner deals with a specific time and place in history, the producers pointed out that the story resonated with young girls anywhere, as they deal with their own situations and circumstances. In Washington DC they attended a screening accompanied by the First Lady of Afghanistan and a young woman who had dressed as a boy during the Taliban era. They hinted at many stories that had been confided in them that they would never be able to share. The film, they concluded, makes it possible for people to bring these things up in conversation.

How did you balance this, Howard asked. Leo said they relied on consultants. It also helped to acknowledge knowing what they did not know. There was no real primary information readily available from the Taliban era, as there was a virtual media blackout at the time. They had no film or photographs to draw on.

The final discussion of The Breadwinner dealt with music and sound design. Twomey stated that they brought the composers in quite early, and that they worked closely with the sound designer. “Sound is 50% of the film,” she said. They went on locations as much as possible, and sound effects were worked into the soundtrack itself. But they felt it was important that the music never tell people how to feel. They purposely left space for silence.

COCO

Pixar’s Coco was third on the program (the films were discussed in alphabetical order). The clip selected was the emotional scene at the climax of the film as Miguel implores his Mama Coco to remember her father Hector. Following the clip Howard introduced producer Darla K. Anderson, who apologized that Director Lee Unkrich was out sick. (There must have been something going around at Pixar.)

Howard began with a compliment on the design of the elderly Mama Coco. He noted that CG animation can easily slip into the unsettling “uncanny valley,” but this was successfully avoided in Coco. The beauty of the elderly woman as she subtly moves through a range of emotions was very powerful in the scene. “When did you know this scene would be in the movie,” he asked.

Anderson said that it was decided on very early in the process. It helped, she said, knowing they had a strong scene to point the rest of the movie toward. It took six years to get there, and all along the way they had to remember the initial feeling that inspired them.

Howard asked how Pixar handled moving from their many fantasy films (Cars, Toy Story, A Bug’s Life) into a world of a real culture, inhabited by real people. “Research,” was Anderson’s prompt answer. They knew they had to depict a real culture engaged in a real cultural celebration. They traveled a lot in Mexico and consulted with three experts. She noted, “Our films are not good until they are.” She said that early screenings were shared with a lot of trepidation.

Anthony Gonzalez, the young actor who played Miguel was the next topic of discussion. Anderson noted that there was an early charge to hire an all Latino cast. There were casting calls in Mexico City as well as Los Angeles. They spent a solid year and a half looking for their cast. Anthony was one of the kids from LA. He was brought in to perform for several scratch tracks. They discovered that his family exuded love, enthusiasm and energy. And he could sing! He was actually performing with mariachis when he was four years old. In the end he got the role.

Howard next touched on the two worlds of Coco—the real world of the Mexican village, and the fantastic realm of the Land of the Dead. How did they go about visualizing that? Anderson chuckled that while Pixar prides themselves on extensive primary research, they could not travel to the Land of the Dead. But they knew they wanted it to be a visual representative of the holiday: beautiful colors, gorgeous music, and celebratory family gatherings. As they visited small villages they were enchanted by the marigold paths that lead loved ones from the cemetery to the homes. Based on this, one of the conceptual artists created the marigold bridge as a link between the two worlds.

Anderson went on to add that making Coco taught her so much about the Day of the Dead. It is intended to not only remember those who came before us, but to remain connected to them. During the making of the film personnel at Pixar started creating ofrendas, shrines of remembrance to past loved ones. Howard noted how moved he was at the assemblage of family photos that formed a part of the end credits of Coco.

Language and music rounded out the discussion of Coco. Anderson credited the consultants with helping them retain much of the original Spanish language. And Coco is the most musical film Pixar has produced this far. They spent a week in Mexico recording every type of music they could gather. Of course, the song “Remember Me” became a major plot point, requiring a song that could be bold and brassy, or heartfelt and tender. That it is nominated for an Academy Award is testament to the songwriting team’s success.

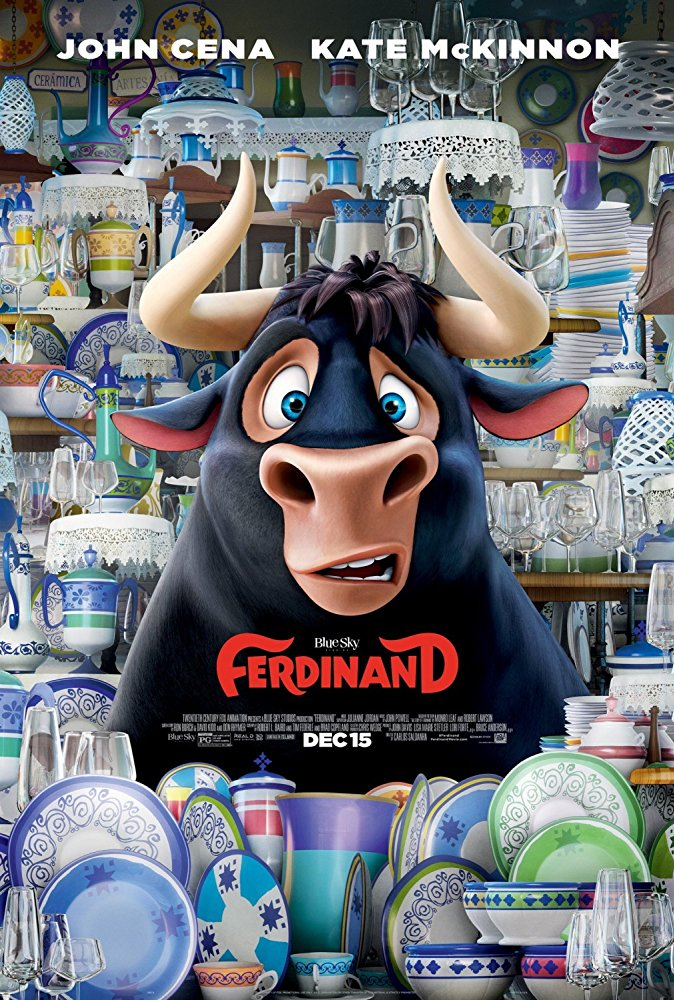

FERDINAND THE BULL

Ferdinand the Bull was next up. The clip veered between high action (a chase on rail cars) and character driven drama as Ferdinand allows himself to be captured to save his friends. This was followed by an extended sequence depicting preparations for the bull ring by the matador and a bewildered Ferdinand.

Howard pointed out that he was not aware that the original book came out in 1936, and the Disney short feature followed in 1938. Were either of these a favorite of filmmakers Carlos Saldana or Lori Forte?

Sanders revealed that Saldana had been working on an idea involving a boy and a bull for some time. Saldana had the idea some seven years earlier, and spent four years actively developing it. When the rights to Ferdinand the Bull were acquired, he was very excited. At the time he was working on Rio. As a native of Rio, he was familiar with the milieu. As Ferdinand was set in Spain, he turned to the family of the original writer. It turned out that the author had never been to Spain. As this was Saldana’s first adapted screenplay, he worked closely with the family to expand the slight story into a feature length film. Howard was intrigued to learn that the live action film The Black Stallion had an influence on Ferdinand the Bull. Saldana pointed out that this was in the fur technology. In early CG fur was a major issue, requiring vast amounts of time and memory. But for Ferdinand the Bull they were finally able to capture the exact sheen of dark fur they were seeking, inspired by the Black Stallion. Howard next asked what other research was employed in Ferdinand the Bull. Saldana mentioned that since the author of the original book was an American had never visited Spain, they did for research.

The original story was very emotional Howard noted, but also very short. How did they go about adding material to make it into a feature length film? Saldana stated that there were two elements that were most important: Ferdinand’s decision to sit down, and the cork tree. The decision to sit down was the target; it was just a matter of getting there. While the obvious message is one of non-violence, there was also an element of pride.

Forte added that they wanted to depict the idea that Ferdinand’s culture—“bull culture”—was rigidly defined, and in marked contrast to Ferdinand’s decision. The big message was to be yourself and stand up for what you believe. Ferdinand, she said, was a character who did not really change, but who changed the characters around him, and his world.

Saldana said that this did not fully prepare him for a research trip to a bullfight in Spain. The event was like a football game, with excited crowds gathering in a festive atmosphere. But as soon as the bull entered his heart sank. He felt such anxiety—for a bull that could not understand what was about to happen.

Howard wound up the discussion with a note on the casting of John Cena as Ferdinand. Forte said they listened to many performers, and were pleasantly surprised to find that John Cena was just right. He had been a “scrawny” kid, and could relate to a powerful character that had a tender side. Saldana added that finding the right voice can really animate a character, and that John Cena’s heart and gentle soul were so unexpected.

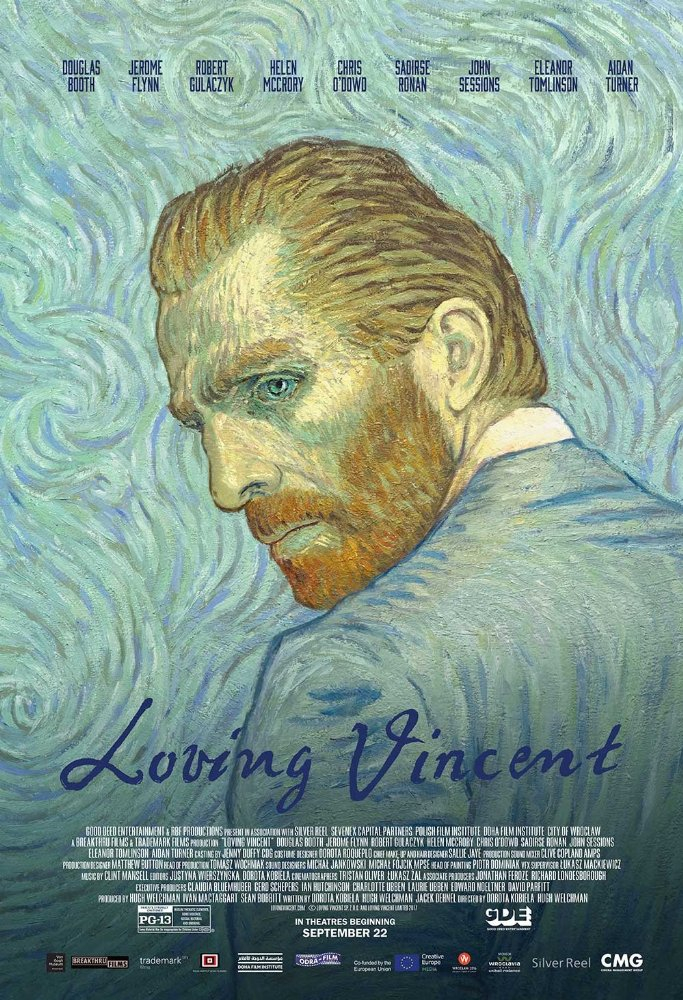

LOVING VINCENT

The final Animated Feature for the evening was Loving Vincent. The clip shown was a revelation—a film animated entirely with oil paintings, in the style of Vincent Van Gogh. The plot revolves around his life as a painter, and an element of mystery surrounding his untimely death. Howard marveled at the monumental task of creating Vincent—over 65 thousand individual oil paintings were created for the film. Creators Dorota Kobiela, Hugh Welchman, and Ivan Mactaggart quickly pointed out that there were actually 850 individual shots, and that each involved over painting an “establishing shot” and carrying the scene to its end. Welchman apologized that there were very few moving shots in the film, but that static shots alone yielded a third of a second of animation per artist each day. It took two weeks to create one second of a scene in which the camera “moved.” The film was in production for 10 years.

Kobiela explained that she had conceived the film as a short subject. She is a fine artist and after reading Vincent van Gogh’s letters at age 16 she wanted to combine her passion for fine art and film. Originally planned as a seven minute short, her plan was to “paint” a film. She applied for a grant to realize her vision, was awarded the funds, but then had to wait to receive her grant. While waiting she traveled to Poland where she met future husband Hugh Welchman. She was surprised and dismayed to discover that he was unfamiliar with van Gogh. (Despite looking just like him, Welchman claimed!) Over ten shots of tequila, she told him the story and he was on board.

Howard moved from the film’s amazing technique to its content. He expressed his surprise that there is a great detective story contained in the plot. He mentioned how Amadeus humanized dusty characters from history for him in his childhood, and said that this film does the same for Vincent van Gogh. Kobiela said that her desire was to break the stereotype of van Gogh as a kind of mad genius, flinging paint and leading a tortured life. Welchman pointed out that van Gogh was not a “natural genius.” He failed at three careers before turning to drawing at 27 and painting at 29. He was not good at communicating with people face to face, but he accomplished this through art. While he was largely unknown in his own lifetime, he has inspired people and artists long since his death. Howard added that van Gogh should be the patron saint of art students. His early work was really rather poor, but his mature work set a new course for art. Howard went into the technical difficulties of getting a project like Loving Vincent made. The filmmakers actually created a Kickstarter campaign. Mactaggart said it was a necessity, as they believe audiences instinctively seek new and exciting forms of art, but film companies want to fund only things that have already made a lot of money. Going to the people was an option in the internet era. Their first goal fell short, so they launched again with a lower target and raised their initial funding. “People either didn’t get it or really loved it,” explained Mactaggart. The Kickstarter also created a germ of a supportive community that saw them through the rest of the process.

Howard’s final question was about finding—or training—125 people who could paint like Vincent van Gogh. Kobiela explained that they first went to fine artists and trained them to animate. To expand the crew they placed a simple video on their recruitment website, detailing how the film was to be made. Unbeknownst to them, the video was picked up by a popular Facebook page and went viral, garnering 2,000,000 hits in a matter of days. They had no idea until friends pointed it out to them. (They stated that the video eventually topped 200 million views.) Following this, applications poured in from around the world. Some actually thought it was a practical joke—that no one would actually attempt to create an entire animated film utilizing oil paintings for each frame.

Byron Howard congratulated each of the nominated teams and welcomed them all back on stage for a free-wheeling discussion of the state of modern animation, differences between live action and animation (“We can erase our mistakes,” one panelist quipped.) and future projects. Many filmmakers stayed after the formal presentation was over to greet admirers and sign programs.