Every now and then something will happen that will inspire a brush with our own mortality. My most recent one of these was prompted when I had the realization that the 25th anniversary of Toy Story is here. Instead of dwelling on how many circles around the sun we’ve taken since the movie debuted, let’s take a look back at the creation of the seminal film from Pixar Animation Studios and the lasting impact it has had.

I’m going to set our time machine for a bit more than 25 years, as that was when the movie was released. The production of an animated film takes years, the average one taking at least four years, and Toy Story was no average film. It was the first full-length computer animated feature. Something that John Lasseter, Ed Catmull, Steve Jobs, and the rest of the Pixar team had long wanted to do since the studio was founded in 1986. There’s a far longer story here that can be saved for another time about the studio’s beginnings, but shortly, most of Pixar’s work at the time was limited to visual effects in other films and commercial work to pay the bills. Having worked with Walt Disney Feature Animation (Now known as Walt Disney Animation Studios) to develop software used and effects in a lot of the films of the “Disney Renaissance,” they were invited to make a featurette for television inspired by the Pixar short, Tin Toy.

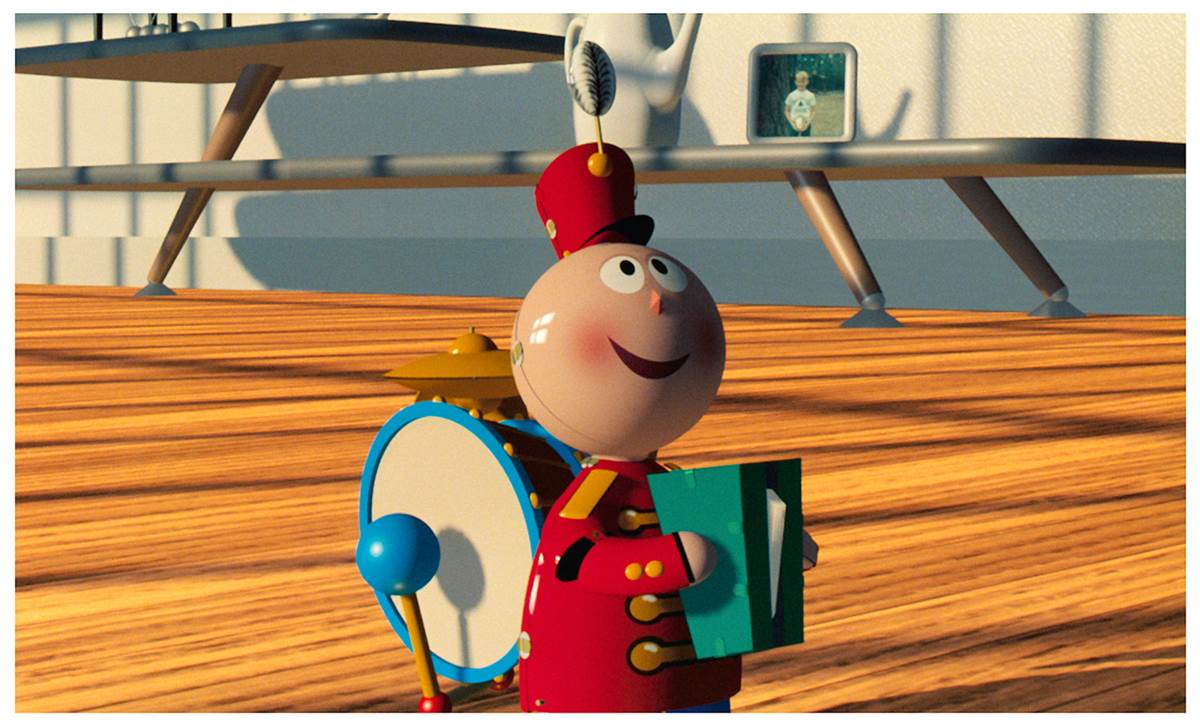

In Tin Toy, we see a drummer toy (Tinny) come to life to avoid being placed in the mouth of a baby while onlooking toys watch the chase in horror. In 2003, the short was adopted into the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and part of the argument that can be made for why, is that it directly influenced Toy Story (also in the National Film Registry since 2005 after 10 years, the minimum age of a film that can be allowed in). It was during the talks for “"A Tin Toy Christmas” that the idea of Toy Story was first discussed.

It was also during this time that Disney, now headed by Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg, were trying to lure back an animator the studio previously fired in John Lasseter to come direct at their studio. Reportedly, he later told Ed Catmull, “I can go back to Disney and direct, or I can stay here and make history.” Realizing that he couldn’t tear Lasseter away from Pixar, Katzenberg set out to make a deal. It was actually a deal for Tim Burton and The Nightmare Before Christmas that gave Katzenberg the idea of signing a different studio to produce a film under the Disney name. The deal that was written could also be the topic of a whole different article, as it became a point of contention years after Toy Story was released.

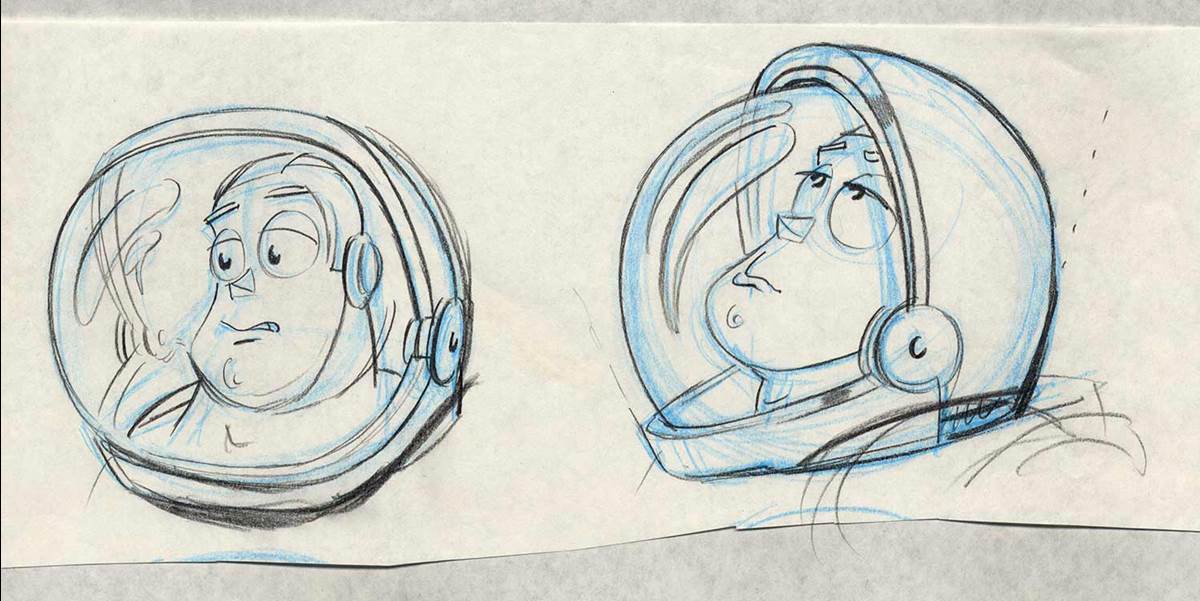

The original concept for Toy Story was similar but vastly different than the film we know today, with Woody as a ventriloquist dummy that was so snarky and sarcastic, what Jeffrey Katzenberg termed “edgy,” that the character gained an immediate reputation in Hollywood circles as being immediately repulsive. Roy E. Disney has also mentioned that the original version felt so long that he would find himself just fast forwarding through video tapes of storyboards wondering “will this thing ever end?” After reworking and retooling, and eventually taking back creative control, John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, Pete Docter, and Joe Ranft landed on the idea of a buddy comedy, with smaller details being changed throughout the writing process. One small detail that became a huge moment in the film was the idea of (who became) Buzz Lightyear not knowing he was a toy. An earlier draft had him knowing he was a toy the whole time.

Courtesy Pixar Animation Studios

At this point we have a script with a greenlight. Time to cast. According to John Lasseter, he always had Tom Hanks in mind to play the role of Woody, citing his ability to convey emotions and make an otherwise unlikeable character appealing. See Also: Hanks’ performance as Jimmy in A League of Their Own. Lasseter had made a quick animation test using dialogue from Turner and Hooch and an early look for Woody that was shown to Hanks.

Courtesy: Bootleg Ultraman

According to Hanks, “They said ‘Look we just want to show you this thing because it's too hard to explain what it is’ and when I saw this loop it was startling, actually, it was kind of like hypnotic. Let’s see it again, can I see that again!? I think I must’ve watched it three or four times. It didn’t look like animation, it looked like plasticine come to life. I couldn’t explain it, even to friends, what it was like. It was going to be this whole new thing, they’ve just invented something that was a brand new way of doing this.”

Of course, Lunar Larry Buzz Lightyear still needed to be cast, and that one was reportedly not as easy as Tom Hanks as Woody. Multiple actors were approached, including Chevy Chase, Jim Carrey, and most notably, Billy Crystal. Crystal declined the role after seeing an animation test saying that the film felt too experimental thinking it was doomed to fail. He later stated it was the one role he ever regretted not taking, but also said he wouldn’t have been right for it. Crystal later went on to provide the voice of Mike Wasowski in a different Pixar buddy comedy, Monsters Inc. saying it was his favorite character he’s ever played.

The role of a more finalized Buzz Lightyear landed in front of Home Improvement star Tim Allen.

“Lasseter called me and said would you look at these sketches of this character that we think you’re the perfect guy for,” Allen said, “The only thing that sold me was his enthusiasm. I said ‘What a neat idea?’ [with] no idea visually what this would look like. He let me stretch it a little bit and really make it this closed-head injury type of guy. He’s full of himself but in a great way. I don't think of Buzz as really obnoxious, obviously, because I think he’s the more popular toy.”

Rare for animation recording sessions, both Allen and Hanks recorded their vocals together, simultaneously. Though only a vocal performance this helps create a more honest and genuine chemistry to appear on film between the two animated characters. The rest of the cast was also set for an amazing ensemble of support characters, including Wallace Shawn as Rex, Annie Potts as Bo Peep, Don Rickles as Mr. Potato Head, Jim Varney as Slinky Dog, and the first of what became a Pixar Animation Studios tradition to include him in every film, John Ratzenberger as Hamm. There was also a role (that eventually became Bo Peep) for Barbie, but Mattel didn’t want to allow one of their most valuable properties in the pioneering film, a decision they would later retract when it came time for Toy Story 2.

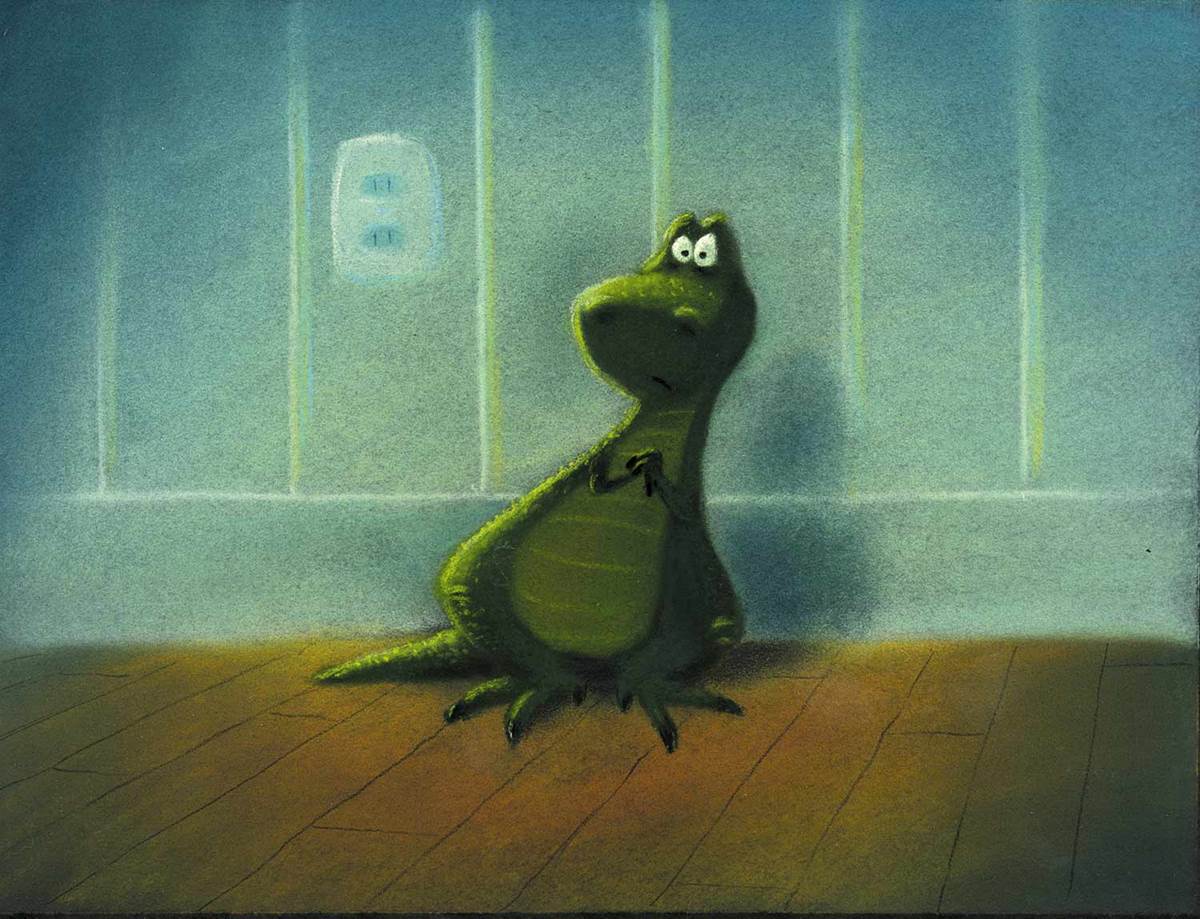

Courtesy Pixar Animation Studios

Keep in mind, at this point in time Pixar was not a household name, and only recognized in certain Hollywood circles but not much else. The staff was nowhere near the size of the studio we know today, and everybody was doing everything together. Animators were working alongside programmers and coders, further strengthening Pixar’s mission: “Artists inspire the technology, technology inspires the art.” Each shot in the film would start at the Art Department, getting its color scheme and lighting before being handed off to the Layout department. Here, models are placed in the shot and camera moves are programmed. Now the shots go to the animation department. At the time, the staff was so small everyone would work on every character unless Lasseter felt the acting was particularly important in that scene. Traditionally, especially at Walt Disney Animation Studios at that time, a team of animators works on a single character and Lasseter chose not to take this approach. The film then passes through final lighting, shading, and the addition of visual effects before finally going off to rendering. Rendering is a critical process in computer animation as it compiles everything from the previous seven stages of production into the final shot. Toy Story used over 300 computer processors to render each shot of the film. The computers that do this are kept in a cold room running 24 hours a day called a “renderfarm.” Toy Story reportedly required 800,000 machine hours and 114,240 frames of animation in total. This production process, though increased and enhanced as the studio and technology grew, is largely the same today.

Toy Story debuted in November of 1995 at the legendary El Capitan Theater in Hollywood, CA, with an accompanying Toy Story exhibit and play experience next door to the theater. This would later become Disneyland’s temporary “Toy Story Playhouse” attraction in the park’s Tomorrowland. Interestingly, Pixar Co-Founder Steve Jobs was not at the premiere. He had actually booked a theater in San Francisco and invited numerous high-profile computer and tech personalities from neighboring Silicon Valley to hold his own screening of the film at the same time. Some believe that this was one of the first instances of a defining line that would come into play some years later of the difference between a “Disney Film” and a “Pixar Film.”

The film opened to audiences everywhere on November 22nd, 1995. The film, putting it lightly, was a massive success. Critics loved it, and more importantly, audiences loved it, and they came by the droves.

“With "instant classic" written all over it, Toy Story, the first full-length feature entirely composed of computer-generated animation, is a visually astounding, wildly inventive winner.” – The Hollywood Reporter

One critic even compared Toy Story to Walt Disney’s first feature-length animated film, saying that audiences now must feel what audiences felt when Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was released.

The aforementioned deal between Disney and Pixar would leave most of the film’s profits in the hands of the Walt Disney Company, forcing Pixar to go public to be able to keep producing feature films. Thanks to Toy Story, Pixar was now a household name and the IPO for stock in the company was one of the most successful in history.

Toy Story has a lasting presence to this day, spawning off three sequels (two of which are critically deemed better than the one before it), numerous theme park attractions and lands, an animated television series, and most importantly, an entire studio of artists that keep producing quality films of the same caliber.

Even though the Toy Story franchise is now 25 years old, thanks to an on-screen universe that has constantly expanded during that time (Toy Story 4 was released just last year) with new characters, new locations, and plenty of material to keep audiences emotionally invested in the plight of these characters that they love, I’m sure we’ll see a lot more beyond now. New additions to the Toy Story realm, like Forky, are as popular as Woody and Buzz were 25 years ago, but with an entirely new generation. Toy Story Toons shorts, Featurettes like Toy Story of Terror and Toy Story That Time Forgot. and short-form series like Forky Asks A Question are sure to keep new stories coming, as well as any other unforeseen projects on the horizon. After all, how many people honestly thought we’d see a Toy Story 4 after the end of Toy Story 3? And just like Toy Story 4, I’ll watch it, and many audiences who love the characters and stories from everything before it will too.

Toy Story, Toy Story 2, Toy Story 3, and Toy Story 4 are all streaming on Disney+