Walt Disney Art Classics Convention 2004 - Part 1

Page 5 of 13

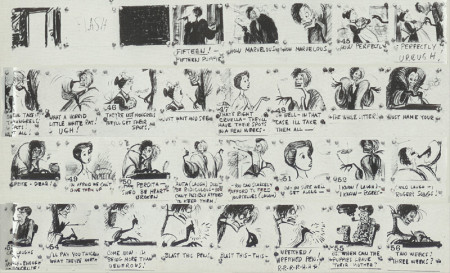

Pacheco chose a memorable scene to illustrate just how the process worked. First he showed Bill Peet’s detailed story board. The sequence began with the moving van full of puppies crossing a one lane bridge. In her car, Cruella attempts to cut them off, but instead slides off into the ditch. After furiously reversing, she slams into the back of the van and (in a moment that didn’t make it into the finished film) climbs over the demolished remains of her car to terrorize the cowering puppies. The sequence ended with a close up of Cruella’s face, twisted in maniacal rage.

An unforgettable image of Cruella’s fury.

Next, a series of photos showing how the model of Cruella’s car was used were shown. Woolie Reitherman, one of the directors, could be seen placing the model car in a scaled down set. Pacheco noted that the sequence never did work exactly as planned. This was, he explained, because of a problem with the “snow.�? Since a heap of shredded foam was used, they could never get the car to stay exactly as placed for the reference footage. As a consequence, the car would “jitter.�? Further, Reitherman’s hand had to remain in most of the shots, requiring them to “sponge it out.�?

After looking at this sequence in detail, Pacheco then showed an image of the latest offering from Walt Disney Art Classics. It was a finely detailed sculpture of Cruella de Vil’s smashed limousine.

Walt Disney Art Classics presents Cruella’s automobile.

Pacheco concluded his portion of the presentation with a few more statistics on 101 Dalmatians. It was released in 1961, at the cost of $14 million. It was estimated that if Walt Disney had done all the work required on the film himself, it would have taken 186 years (which means we would be looking forward to its release in 2143AD). If all the individual animation cels were laid end to end, they would stretch from Los Angeles to San Francisco and back. Enough paint was used on those cels to cover fifteen football fields.

And, Pacheco noted, there were already many “dog expressions�? in the English language at the time of the film’s release. He cited a dizzying list, including “a dog’s age,�? “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks,�? “dog tired, “hair of the dog,�? “salty dog,�? and ended by saying there were too many to record. He then concluded his “dog and pony show�? by introducing Professor Andreas Deja to discuss Animation Techniques in 101 Dalmatians.

The feature animator entered and signed in as Professor Ludwig van Deja on the chalk board. An offer to deliver his lecture in German elicited laughs from the appreciative crowd.

Every animator, he began, works in his own technique and style. For 101 Dalmatians, though, a single style would be used throughout. The line work of English artist Ronald Searle was the inspiration. As he showed examples of Searle’s work, he explained that while Searle was invited to participate in the creation of 101 Dalmatians, he was unable to do so.

Andreas Deja showed numerous examples of the work of Disney’s greatest

animators.

Deja then lauded the “incredible story man Bill Peet.�? He pointed out how closely the finished film followed Peet’s conception. “I don’t know any other story artist who is this accurate and thorough,�? he said.

A portion of the detailed storyboards created for 101 Dalmatians.

He also enthused over Peet’s character designs. It was, however, Milt Kahl (described by Deja as “a master draftsman) who refined those designs. Deja showed a series of each artist’s drawings. He pointed out that Bill Peet didn’t like the nose on Kahl’s Pongo, saying it looked like it belonged on a Great Dane. After some good natured quibbling, and a test sequence, Bill Peet prevailed. Kahl went on to produce all the key drawings that would be used by all the animators in order to maintain a consistency in style.