The Art of Star Wars: How Lucasfilm’s Artists Keep a Galaxy Cohesive and Cinematic

At LightBox Expo’s The Art of Star Wars panel, moderator John Romulo of the Lucasfilm Art Department convened concept heavyweights Jama Jurabaev, Benjamin Last, and Andrée Wallin for a candid look at how Star Wars’ worlds come together, often under crushing deadlines, heavier-than-earth assets, and the mandate to keep a 40-plus-year visual language feeling fresh. From the first moments, one theme set the tone: Doug Chiang is the north star. The artists described Lucasfilm’s executive creative director as the “gatekeeper” whose concise, constructive notes both protect the brand’s visual DNA — graphic silhouettes, readable shapes, clear staging — and free them to explore.

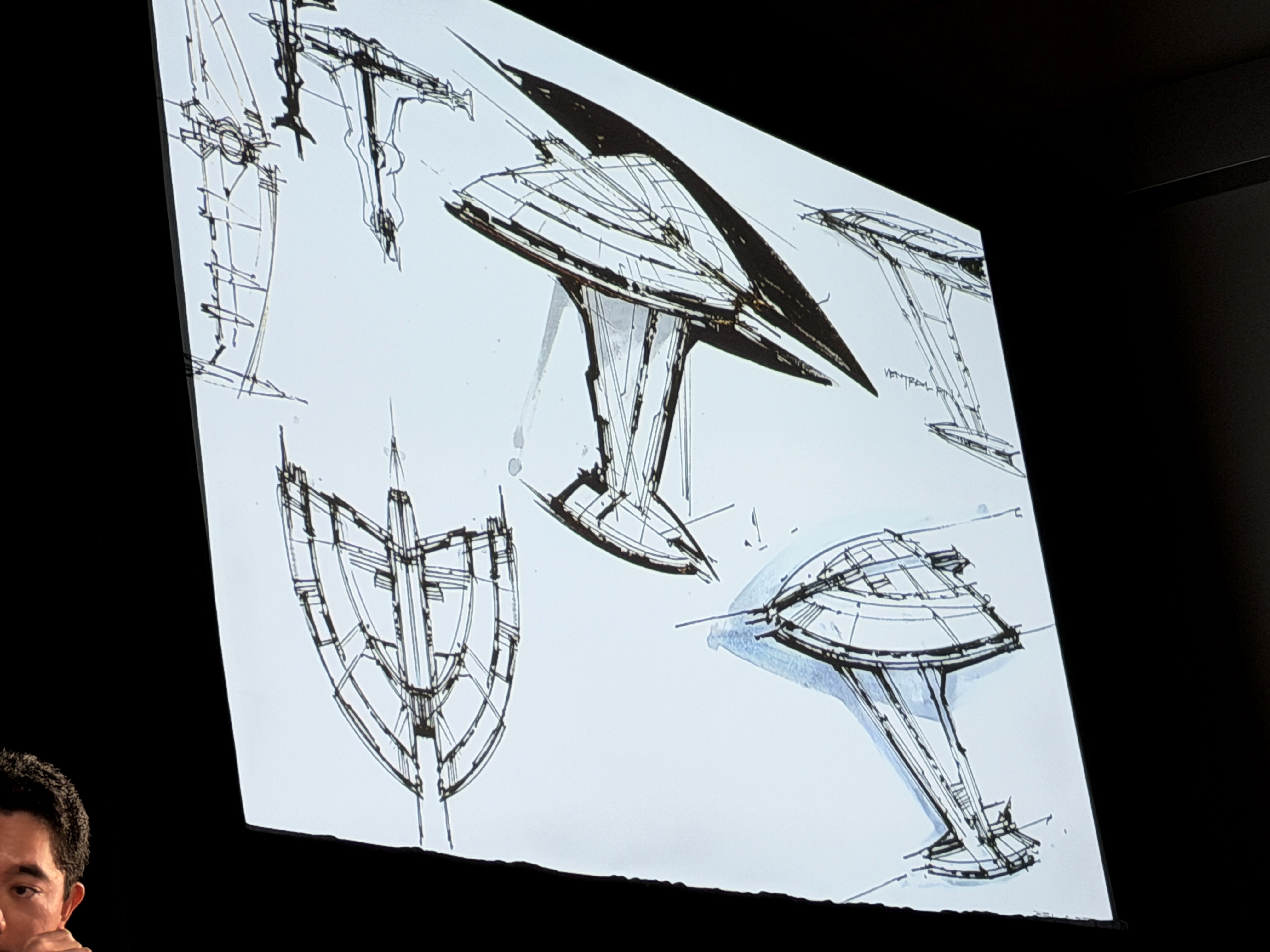

Jurabaev kicked off with a war story from Skeleton Crew: an enormous starport that turned “nightmare” the second his Blender scene crashed. The only path forward was a mid-assignment tool swap to Unreal Engine — his first ever Unreal project — to keep iteration speed high enough to land approvals. If that project embodied the pain of scale, Last countered with a rare “easy” win: a luxury spa planet keyframe that flew through approvals because the ship designs, pitched with a John Berkey vibe. had already been solved. For Wallin, best known for painterly 2D keyframes and environments, Ahsoka brought an unexpected first: creature design. Riffing from animation canon and nudged by production design notes, he discovered how different creature briefs are from environments, and how liberating it can be to step outside your lane.

Across their anecdotes, the panel kept returning to what makes Star Wars look like Star Wars. Chiang’s most useful maxim, they said, is to simplify the read: reduce a design to a bold, legible silhouette, then tuck the “agreeables” — greebles, paneling, grime — inside that big shape. Cinematography matters as much as design. You can stage an opening wide that screams “epic,” but if the background scale overwhelms the mid-shots that follow, your dialogue scene dissolves into a gradient. The trick is balancing grandeur with character readability so the cut-ins still sing.

Process-wise, the trio illustrated how different toolsets can arrive at the same cinematic truth. Wallin works almost entirely in 2D, using occasional 3D plates as raw material to paint over; that speed lets him explore a wide slate of ideas in a short span. Jurabaev and Last lean into 3D (Blender, Unreal), then paintovers for polish, which pays dividends for lighting studies, mood, and quick reframes. Whatever the path, the daily cadence is the same: upload roughs, block-ins, sketches, and polished frames to a shared folder. The time-zone offset creates a “friendly rivalry” — opening the folder to find a teammate’s 15 jaw-droppers can sting, they admitted, but it raises the bar and accelerates solutions for everyone.

The practical hurdles are as Star Wars-sized as the stories. Hero ILM assets are often too dense to move inside a concept timeline, so the team will project a few renders onto planes, kitbash lighter elements (a combination of different models, objects, or images), or even grab a marketplace model to keep momentum. Fidelity gives way to the actual goal: a finished, readable story beat the broader crew can execute against. The software is an ingredient; the frame is the meal.

Audience questions turned the conversation toward canon and cohesion. Designing new worlds — Peridea in Ahsoka, for instance — starts from Ralph McQuarrie’s DNA and grows outward. The job is less about reinventing the universe than finding fresh angles that feel inevitable once you see them. Chiang provides the rails and references, but the artists stressed their parallel responsibility: understand the client. Early in a show, listen for the references that recur; those repetitions map the director’s taste faster than any style guide.

For aspiring artists, the advice was refreshingly analog. Step away from algorithmic image feeds and go back to books — architecture, manufacturing, biology, old mechanical manuals — so your visual library isn’t just yesterday’s trend with a new coat of paint. Study film language to understand why certain frames stick. If you love keyframes, show them, but accompany each hero image with process: roughs, block-ins, and design explorations that prove you can originate ideas, not just illustrate them. And perhaps the most actionable tip of all: be prolific, be persistent, and be kind.

The panel closed where it began, on the strange alchemy of consistency and change. Star Wars remains cohesive because its visual rules are simple and cinematic, and because artists like Jama Jurabaev, Benjamin Last, and Andrée Wallin treat those rules as a foundation for invention rather than a box. Whether the shot is a painterly 2D keyframe, a real-time Unreal vista, or a kitbash projected onto a plane, the mandate never changes: make the story read in one glance, and make sure the characters still own the frame when the camera moves in.