30 Years of A Goofy Movie: How a TV Spinoff Found Its Heart

A Goofy Movie director Kevin Lima reunited with Jim Morgan, Brian Pimental, Chris Ure, and Steve Moore at LightBox Expo for a 30th-anniversary conversation packed with scrapbook treasures — story reels, demo songs, and boards — that traced how a gag-driven Goof Troop spinoff narrowed into the father-and-son road movie fans love today.

The earliest mandate sounded like a TV extension: “a bunch of little vignettes and catchy songs” strung together, more Naked Gun than Disney fairy tale. Early drafts hauled in the entire Goof Troop cast (including Peg and Pistol), plus neighbor subplots and side-gag runners. It played funny in isolation, but the feature kept bogging down under the weight of an ensemble built for episodic stories.

The turning point came with a simple reframe — make it “a story about fathers and sons.” That clarity set up two mirrors: Goofy struggling to connect with Max, and next-door neighbor Pete modeling the most dysfunctional version of parenting imaginable. Once that spine locked, the movie systematically shed everything that didn’t push their relationship forward.

One formative pitch session with Jeffrey Katzenberg crystallized the course correction. Faced with a board sequence built for laughs, Katzenberg blitz-scanned the wall and cut to the core: where’s the emotion? The team pivoted: fewer blackout gags, more moments that expose Goofy and Max’s wants, fears, and misreads. That “heart first” filter later guided everything from what jokes stayed to which characters simply had to go.

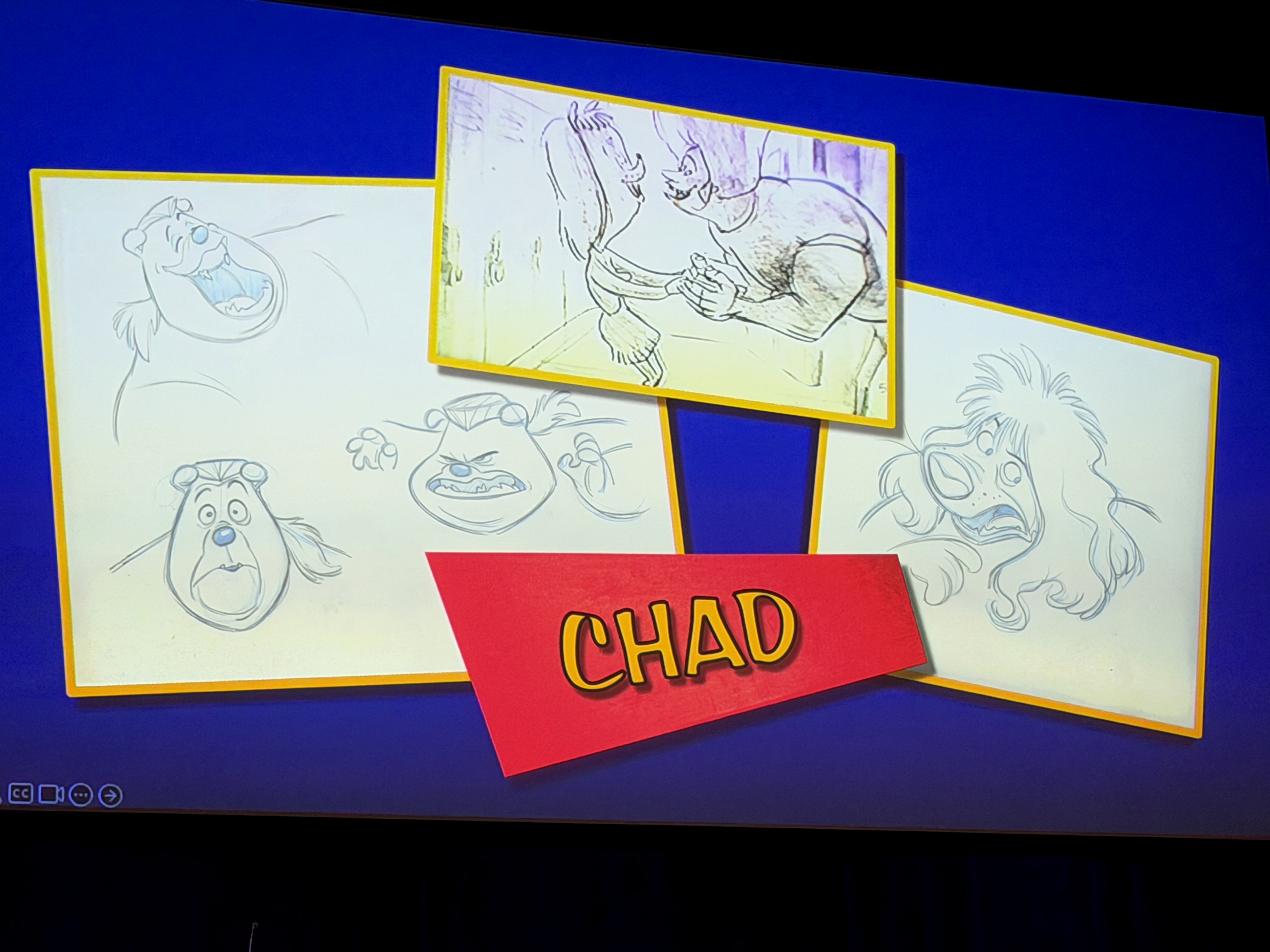

Among the casualties was Roxanne’s would-be rival suitor, Chad, a swaggering foil designed in part by The Proud Family’s Bruce W. Smith. Chad even made it to dialogue tests, with Joey Lawrence (fresh off Blossom) reading the role. In early scenes he needles Max, bluffs about asking Roxanne to Stacy’s party, and escalates Max’s lie into a TV-concert ultimatum. Ultimately, the character duplicated pressure the plot already had (Max’s lie + the road trip), ate precious screen time before “On the Open Road,” and diverted focus from the film’s central relationship. Chad’s final design didn’t go to waste — you can spot a look-alike tucked into the “After Today” sequence.

Another pair almost minted as recurring road-trip foils: Wendell and Treeny. A killer first gag had Goofy misreading Treeny’s bungee jump as a suicide attempt and “saving” her mid-plunge. In the outline they kept reappearing, including at a water-park that Max would’ve snuck into after the disappointment of Lester’s Possum Park. The compromise is what audiences see: Wendell and Treeny survive as visual Easter eggs — the oddball romantics in “On the Open Road,” then quick cameos at the Powerline finale (“I2I”), with Treeny as a backup singer and Wendell on the road crew. It’s a wink, not a subplot.

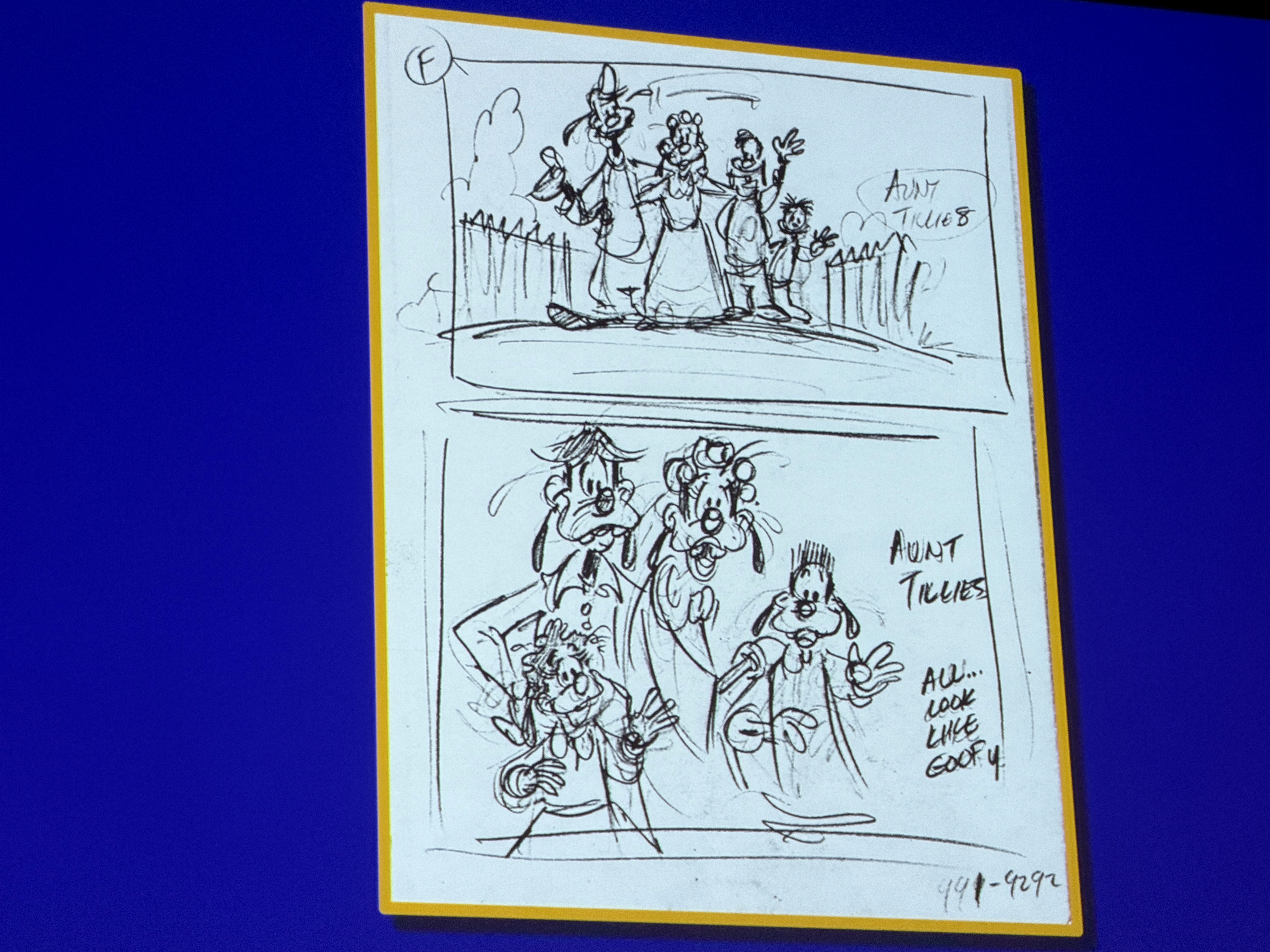

One abandoned mid-movie detour took Goofy and Max to Aunt Tillie’s for a full Goof family reunion — the joke being that every relative is unmistakably “Goofy,” down to crickets at the homestead chirping a dead-on “hayuck.” It was charming color, but again, the feature’s pacing test is brutal: if a stop doesn’t bend the father-son relationship, it’s a scenic delay.

The crew also previewed a storyboarded deleted song written by William Finn. The number had Pete gleefully taunting Goofy with Max’s doomed future, spiraling into a surreal sequence where Max goes to literal hell and winds up in an electric chair. The set-piece proved too much — tonally and time-wise — but one image survived as dialogue: Goofy’s fear that Max will end up in “the electric chair.”

The artifacts screened at LightBox are riotously funny — Chad’s posturing, Treeny’s bungee chaos, Aunt Tillie’s hayuck chorus, even Pete’s infernal patter — but the final film works because the team protected the spine. Each excision sharpened the line from misunderstanding to honesty between Goofy and Max. The result isn’t a collage of great gags; it’s a coming-of-age road movie where every element works in service of one truth: sometimes the scariest leap isn’t onstage at a concert — it’s telling your parent who you really are and “for the first time ever, seeing things eye-to-eye.”