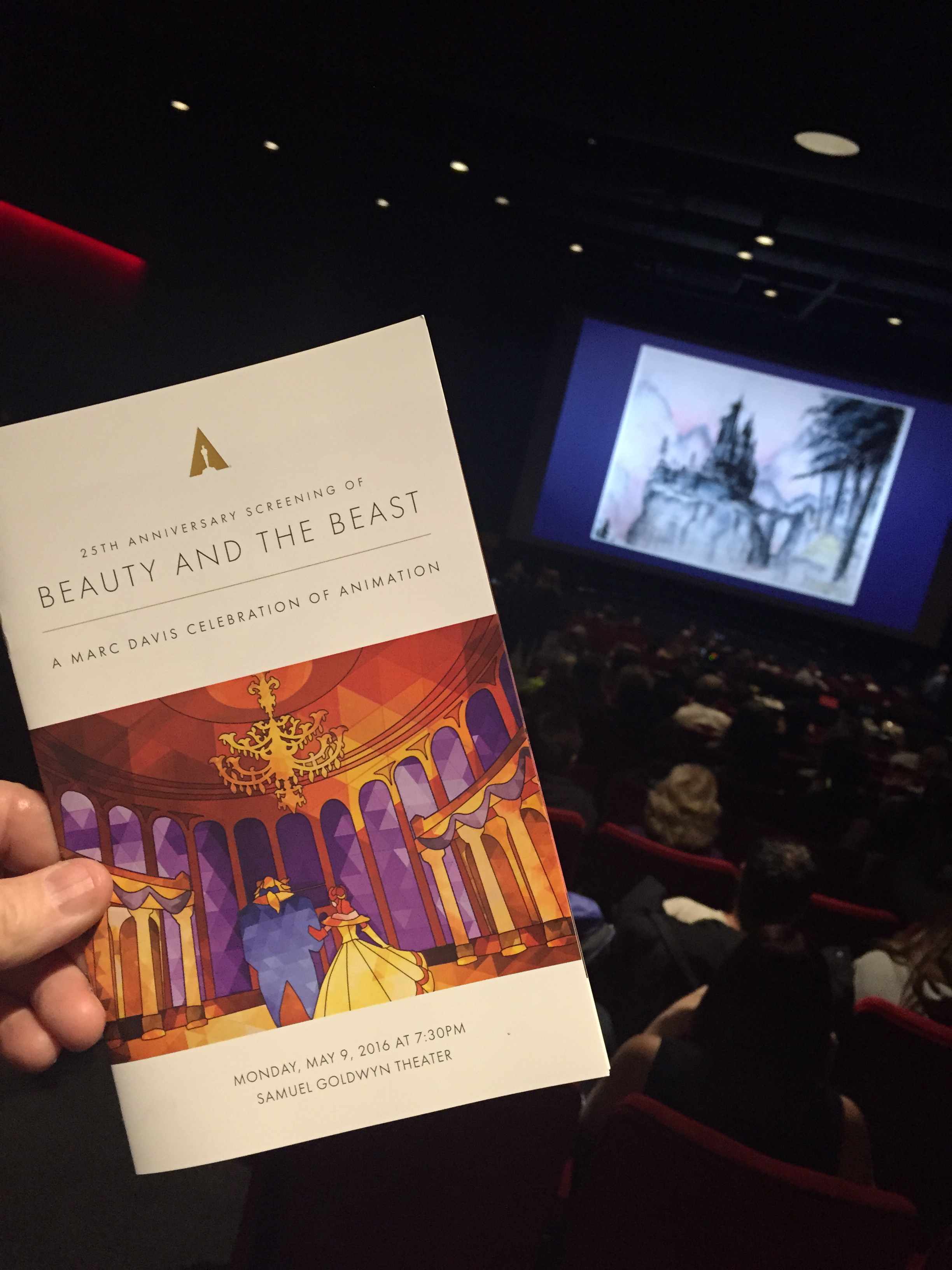

Although Disney’s Beauty and the Beast will mark the 25th anniversary of its debut this October, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences earlier this month kicked off the celebration with a screening of their 70mm print. Offered in the ongoing Marc Davis Celebration of Animation, the evening included a distinguished panel of guests connected with the making of Beauty and the Beast.

Randy Haberkamp, managing director of the film preservation program, opened the evening by welcoming the crowd that filled the AMPAS Samuel Goldwyn Theater. He explained some of the work of that the AMPAS does in preserving films, an effort that was also celebrating its 25 anniversary in 2016. Over 1,000 films have been preserved through these efforts. The print for the night’s screening had been presented to the Academy by the Walt Disney Company, and, Haberkamp said, would be shown exactly as it was seen in 1991 by audiences who said, “Yes, this is a Best Picture nominee.”

Beauty and the Beast has the distinction of being the first animated film ever nominated in the Best Picture category and at a time when only five films were chosen for the honor each year. Since then only one other animated feature, Up, has been nominated. Today, Feature Animation has its own category, so it is unlikely any others will be nominated in the Best Picture category. Although, Haberkamp noted, at the rate that CGI and other enhanced technologies were being used in live action features, the two genres were moving toward each other.

In speaking of the Marc Davis Celebration of Animation, Haberkamp said how glad he was that Disney had not completely abandoned animation, as they had threatened to do in the late 1980s. He noted that it was Beauty and the Beast, The Little Mermaid, and The Lion King that had kept classic Disney animation alive. He introduced Marc’s wife Alice Davis, who rose to accept an extended round of applause from the crowd.

In thanking Alice Davis, he noted that although she had not been invited to be a Disney animator, she did contribute to the Company by designing costumes for the theme park attractions. “Alice finds a way,” he said. He added that he hoped she would pursue writing an autobiography, offering the advice, “Don’t hide. Be part of the story.”

Just before bringing out the panel, Haberkamp also thanked Howard Green, Theo Gluck and Liz West for their help in assembling the evening’s program, as well as the Disney Animation Research Library for providing rare concept art that was shown on the screen as the audience filled the auditorium. Finally, he offered a “tip of the hat” to Roy E. Disney, for keeping Disney animation alive.

Haberkamp chuckled that all films for these kinds of screenings should be 84 minutes long. This left enough time for the discussion before hand, despite the fact that the kids were waiting. Panelists for the evening were: producer Don Hanh, director Gary Trousdale, story supervisor Roger Allers, key story artist Brenda Chapman, Paige O’Hara (Belle), supervising animator for Belle Mark Henn, Robby Benson (Beast), supervising animator for Beast Glen Keane, David Ogden Stiers (Cogsworth), Richard White (Gaston), supervising animator for Gaston Andreas Deja, and Angela Lansbury (Mrs. Potts). As the group settled into their seats (playing a little “musical chairs as they did so), Haberkamp noted that he could have filled the stage twice over with all the talented people available that had worked on the film.

The conversation opened with Glen Keane, who, Haberkamp noted, had started working on Disney’s Beauty and the Beast in London with a different set of directors. Keane admitted that this early effort was “a pretty wonderful time.” He recalled strolling London with his family, sketchbook in hand. They were making a very European version of the story, led by the talented Richard Purdom, but it was not very “Disney.” Walt, he pointed out, would take European fairy tales to California to make them into Americans. And so he found himself headed to Florida to meet with Jeffrey Katzenberg, the head of the newly revitalized Disney animation division.

There he was given bad news and good news. The bad news was that everything they had produced was being thrown out. The good news was that he would get to spend three more weeks in Europe before everyone was moved back to the States. Keane spent the three weeks touring France and soaking up atmosphere for the newest version of Beauty and the Beast.

It was at this time that the decision was made to turn Beauty and the Beast into a full-scale musical. Producer Donn Hahn explained that this was due to, “a little film that came before us, The Little Mermaid.” Howard Ashman and Alan Mencken had brought Broadway to Hollywood, and they were now to apply their magic to this project. Hahn took a moment to speak of the late Howard Ashman, stating that he was more than a lyricist; he was a mentor, a coach, and a booster. Ashman’s many contributions were spoken of repeatedly throughout the evening.

In turning to director Gary Trousdale, Haberkamp pointed out that the fledgling director at that time had but a single completed project to his credit, co-director of Cranium Command featured in the Wonders of Life pavilion at Walt Disney World’s Epcot. Trousdale said the unexpected offer to direct Disney’s next theatrical feature was, “a happy surprise to say the least.” After the hectic 90-day production schedule on Cranium Command, he and Kirk Wise were settled into “daycare,” looking for another project as development artists. When he was asked, “Can you and Kirk be on a plane to California to direct Beauty and the Beast,” he thought it was a prank. At the very least, he was looking for the candid camera. He concluded, “We didn’t screw up Cranium Command, I guess.”

Story supervisor Roger Allers was asked about Howard Ashman’s contribution to the development of the film. Allers immediately stated that Ashman’s work ranged far beyond that of lyricist, and into every aspect of the production. He recalled that the original concept for Mrs. Potts popped fully formed from his head, complete with the casting of Angela Lansbury. While Disney had experience doing stories, Ashman gave them his thoughts, complete with amazing dialogue and “very persuasive” suggestions throughout the making of the film.

Allers described one story session as terrifying but thrilling. After the first full pitch of “Belle,” the song that opens the movie, there was a vocal climax featuring the villagers. Allers suggested that it, “needs another layer.” Ashman coolly requested that he supply it. Allers did and they used it in the final film.

Haberkamp then turned to key story artist Brenda Chapman, saying that it was as if she and Roger Allers shared one brain while planning the film. She spoke of the sequence in which Belle nurses the Beast after the wolf attack. It was, she said, inspired by the relationship between Tracy and Hepburn in their films. Belle could see how jumpy he was as she washed and bandaged his wounds. He was really a big baby. If he let out a yell, she’d just yell back at him. Chapman was pleased to recall that Ashman loved their pitch for the sequence.

The supervising animator for Belle, Mark Henn, was commended for all the work he had to do. “She’s in the whole movie,” Haberkamp said. Her character, he added, made strides in the portrayal of women in Disney animated films.

After a shout out to fellow Belle animators James Baxter and Lorna Cook in the crowd, Mark Henn recalled that he was the “head Belle guy” when they were working on the film in Florida. He pointed out that Belle is probably the oldest of all the Disney heroines. As such, she is not looking at the world as a new place, but is rather comfortable with herself and her place caring for the father that she loves. She does not fall in love with the Beast at first sight. It is the fact that their relationship grows that makes the film so magical, Henn concluded.

Paige O’Hara, the voice performer for Belle was asked for her recollections of the recording sessions. “Oh, it was amazing,” she promptly replied. She was there for the first performance of the title song by Angela Lansbury, and said there was not a dry eye in the house. O’Hara noted that the first take was the one used in the film. She approached the prospect of working on the project with Lansbury with some trepidation. Years earlier, on her first trip to New York City she would sneak into the theater to see the second act of Gypsy, starring Angela Lansbury.

Belle, O’Hara said, was an amalgam of the talents of so many people. “They all share Belle with me,” she said. She went on to say that she had never worked on any other project where everyone had the same vision, and everyone sacrificed to achieve it. That is why, she stated, “It is going to be a classic for all time.”

Turning to the Beast, and back to animator Glenn Keane, Haberkamp asked about the character’s complex design. Keane said that his London sketchbook was an important source of inspiration. Daily, he would walk past the Regent Park Zoo. He noted the curve in the back legs of the wolves. He sketched a mandrill named Boris. He laughed as he recalled an English woman’s reaction to Boris’ colorful hindquarters: “He’s got a rainbow bum, he has.” Keane hastened to add, “Not to say the Beast had… well, we never saw his… well… Bell was surprised.”

Other helpful aids from the zoo included a buffalo head and a wild boar’s head. There was a sadness, he said, to the buffalo head. And then there was, he recalled, the gorilla. He wanted to know just what it was like for Belle to be face-to-face with the Beast. He asked if he could get into the cage with the gorilla. (Producer Donn Hahn interjected, “My expense account was weird that week.”) While Keane never did get his face-to-face with that gorilla, he did gain inspiration from another named Caesar. As the ape glowered in a dark corner of his cage, Keane realized he didn’t want anyone to see him.

In casting the Beast, the story was told of a series of unidentified voices on a cassette. Each one was a different actor. Only one was tender, conflicted, warm, and deep. Said Don Hahn, “That was the Beast.” He was told, “Well that’s Robby Benson.”

Haberkamp recalled one of Benson’s early films, Jeremy, in which he played the title role. Jeremy, a shy, bespectacled young man was not what people expected when they thought of the Beast. “How did you do this?” Benson was asked.

Robby Benson prefaced his comments by saying that the script was unlike anything he had ever seen in animation. It read like a Broadway show. He asserted that he never thought of the Beast as a cartoon. “That’s a bad word,” he added.

In the audition, Benson was kind of shocked when he walked into the room and there were two technicians and a Walkman. He did feel that, even if it was “Robby Benson” typecasting, he should play it honestly. But as a person who had worked as a soundman, he wondered how many other actors had roared and growled their way through the part, not realizing so much of that would get lost in the compression of the Walkman recorder. So, he said, his decision was, “Play it from the heart and understand the technology. I got the job.”

Although Paige O’Hara had described the recording of the title song, Haberkamp asked for Angela Lansbury’s impressions of that event. Lansbury stated that her first inkling of the role was a call from Alan Menken and Howard Ashman. Although she did not know them at the time, she was intrigued by the idea they presented her: a lovely movie, a fairy story in which she would play Mrs. Potts. A teapot. “Glad you clarified that,” she told them.

They then went on to play her a song they had written. It was the title track, performed in a mellow rock style that Lansbury felt was not quite appropriate. “Send me the music,” she said, and she would sing a more “realistic” version of how a teapot would sing it. “I did my version and I’m happy to say that version became the version.” Lansbury mischievously noted that she had had a lot of experience with teapots—and even more after people began sending them to her after the film came out.

Lansbury spoke warmly of Beauty and the Beast and its creative team, saying she was happy to have been in a great Disney movie. As for the public reaction, she said, “I’m happy to say they grabbed it hook, line and sinker.”

The inspiration for Mrs. Potts, she said, was a woman she knew when she was young, a little lady named Beatrice, though they always called her Beatty. Her warn cockney accent had many notes; Lansbury said she used them all. Mrs. Potts, she said, was written magnificently and wonderfully animated. “Mrs. Potts became one of the most important characters I portrayed in motion pictures,” she concluded.

Producer Don Hahn brought up the day the song was recorded. Lansbury was flying to New York for the session when her plane was grounded in Las Vegas due to a bomb scare. He explained, “I said, ‘Let’s do it tomorrow,’ and she said, ‘No, no, I’m coming in.” She came in, greeted the orchestra, went into the isolation booth and sang the song just once. It was perfect and we put it in the movie.” Lansbury added, “It was so grand to sing with the New York Philharmonic.”

David Ogden Stiers was asked how it was that his character, Cogsworth, got to improvise so much. “I don’t recall being asked to improvise,” he replied in mock dismay. Lansbury joked back, “Give him an inch, he’ll take a yard.” Stiers went on to say that he enjoyed his many ad libs, and some of them were actually kept in the film. As an example, he stated that the line, “Flowers… chocolates… promises you don’t intend to keep,” was one drawn from life.

Stiers also joined the others in lauding Howard Ashman. He recalled working on the battle scene, in which most of the actors got to record together with the orchestra. Ashman was ill, Stiers noted, so he reached over and took his hand. His voice dropped as he said, “His grip is still in me somewhere. This was a diamond bright and lasting moment in artistic achievement.”

As the discussion turned to the subject of Gaston, Haberkamp described him as the villain of the piece. Voice actor Richard White quickly corrected him, saying Gaston was not a villain. Rather, he was merely… misunderstood. Gaston, he continued, was unusual in the Disney canon in that he was not an ugly protagonist, but was sometimes charming and even invested with attractive qualities. White reacted with mock dismay as his observations drew laughter from the audience.

The contribution of Howard Ashman was again brought up, as White explained that the lyricist was the first to introduce Gaston to White. It started with a verbal description, then sketches, and then discussion of how to embody him. White described it as a wonderful place to start, that Ashman had a way of bringing characters to life and that he could play every one of them. “I got the opportunity to revel in that,” he mused.

For Andreas Deja, the supervising animator of Gaston, the challenge was first in animating a human, then in animating one as a good-looking villain. Visually, the character started out as a caricature, a Captain Hook type with a long jaw and exaggerated manners. After viewing the first rough scene, Jeffrey Katzenberg said, “He’s not handsome enough.” Deja countered that they were going to end up with a soap opera star, and admitted, “I got a little pouty.”

Katzenberg explained that the basic story was to not judge a book by its cover. The Beast was ugly, but beautiful inside; Gaston was handsome, but evil inside. He did offer, “We never said it would be easy.”

Haberkamp then asked about one of the more amusing aspects of the film’s creation, what he referred to as “the chest hair story.” Andreas brought laughter to the crowd as he described the manner in which they illustrated the lyric, “And every last inch of me’s covered with hair.” Deja had depicted Gaston tearing open the front of his shirt, leaving the details to his assistant. In the first test screening, the result was an unusual arrangement of neatly curled chest hair that looked strangely out of place. As others made suggestions, it became something of a competition. Finally, they arrived at the correct visualization of the first ever on screen Disney chest hair.

As the panel portion of the evening wound down, Haberkamp asked for a few thoughts on the striking design of the ballroom sequence that illustrated the title song. Don Hahn described the art direction as brilliant, complimenting the way the ballroom and the costumes gave the sequence the sweep of a true film. He spoke of a late night meeting to design Belle’s ball gown, and how they settled on yellow to complement the Beast’s blue and gold suit. Later he thought about the fact that a bunch of guys eating pizza late at night had designed the ball gown that every little girl in America was wearing as a costume the following Halloween.

Story supervisor Allers spoke of the opportunity they had to explore the ballroom through the relatively new medium of CGI. For the first time they could thoroughly explore a three-dimensional environment, even moving the camera all the way up to the ceiling. Story artist Chapman said that as Allers would move the camera up, she would pull it down Together they really challenged the cameraman. During these sessions, basic shapes were used to represent the characters as they moved through the space. Later, hand drawn animation was added.

Lansbury marveled that it was the first time audiences had seen that in animation, a scene so huge in scope that it was astonishing. Belle animator Henn added that there was a backup solution—an “Ice Capades” effect with the two characters in a simple spotlight. “Thankfully,” he said, “the computer guys made it work.”

There was a final question for Angela Lansbury, asking her to sum up Mrs. Potts. “She’s in love with love,” she said. Mrs. Potts was going to see to it that Belle and the Beast got all the help they needed to fall in love. “And of course,” Lansbury concluded, “she succeeds.”

Haberkamp thanked the panel for sharing their memories and then announced that there were a few more members of the production team standing by for introductions. Referring to them as the “Class of 1991,” he brought them out one by one for acknowledgment, and a final mass photo. The group included Bradley Pierce (Chip), Jo Anne Worley (Wardrobe), Ed Ghertner (layout supervisor), Greg Griffith (digital artist, Ballroom), Jim Hillin (CGI supervisor), Max Howard (studio executive), Burny Mattinson (story), Mark Myer (supervising effects animator), Tony Bancroft (animator for Cogsworth), Dave Bossert (supervising effects animator), Nik Ranieri (animator for Lumiere), Will Finn (supervising animator for Cogsworth), Jesus Cortes (assistant animator), Dorothy McKim (production supervisor), Scott Johnson (computer animation software), and Tony Anselmo (animator for Wardrobe).