In the second part of my interview with George Lucas: A Life author Brian Jay Jones, we discuss the past, present, and future of Lucasfilm in celebration of the company’s 50th anniversary.

Mike Celestino, Laughing Place: How would the pop culture and filmmaking landscapes look different today, if George Lucas hadn't gone into the industry?

Brian Jay Jones: I think it's a double-edged sword, in a way. One of the things that people love is when movies come out now and they're like, ‘Every effect in this is practical’ If you're a movie with practical effects, you're the novelty act now. We've come to appreciate the actual tactile part of filmmaking because of that. Because when we do see a movie that has practical effects and sets are built and so on, there's something about it that our eye catches. Even with the best CGI around, for the most part we can still tell when something’s CGI. And it's gotten way better. I remember seeing the first Spider-Man in the theater and there are parts of that that just look so terrible. And you can watch Lucas in his career, as he's developing CGI. You get to something like Red Tails, the digital effects of that movie almost don't even look finished at times, but the tech has gotten better and better.

Lucas gave us the tech and other people took it and ran with it. So God bless the human beast. We’re able to use imagination and creativity and [we’re] continuing to make that tech better, and it allows us to do a lot of really great things in filmmaking. The season [two]] finale of The Mandalorian, that's something you can do with great CGI tech that you couldn't necessarily do with practical. Maybe you could, but it might not have been as effective. So Lucas has opened that door for better or worse for us, and it's one of those [things] again where filmmakers need to decide how they want to use their powers for good. I think we're starting to see the pendulum swing a little bit. It used to be that everybody was doing everything digitally; no sets were ever built. You'd see these poor actors standing in this ocean of greenscreen, wondering how the hell they were going to know what they were looking at.

We've started to swing the pendulum back a little bit now where we're getting more practical sets and more practical effects. It's easy to be a cynic on this, but I think what [Lucas has] really done more than anything else is, he's given filmmakers another tool at their disposal. I think that, more than anything, is what Lucas really wanted: to give you these tools so you can make the kind of movie you really want, and make it look exactly the way you want. And that's another similarity between Jim Henson and George Lucas. Jim Henson, for example, loved the little handycams when those were first invented in the late '80s. He even said something at the time– what he loved about it was anybody could be a filmmaker. There was nobody compromising your vision; you could make the kind of movie you wanted to with this little handycam. That's the same vision George Lucas had.

CGI tech lets anybody be a director or a sound engineer or whatever, because the tech is there now. You make it look the way you want to look, and I think that's a huge contribution. I think that's one of the things that Lucas remains the proudest of– he's invented that tool. And now that the novelty is worn off, it's just another tool in the kit.

LP: Right, and I think what Jon Favreau is doing with The Mandalorian is he's marrying the progress that Lucas made in the digital arts and then bringing that back toward the practical stuff as well. It's the best of both worlds in that way.

Jones: That is a fantastic example. Favreau in The Mandalorian does what Lucas intends for filmmakers to do. He's got the built sets, he's got practical effects, but he's also got the CGI that he's using when it helps the story. Lucas, in the first of prequels, just falls in love with that tech. He's like, ‘I can make as many spaceships as I want,’ so he puts every spaceship up on screen. Had Lucas continued to make films, I think even he would've backed off the special effects after a while, but he was just so in love with that CGI. It was the brand new toy back in 1999, and he was going to use it as best he could back then. But I think [with] something like The Mandalorian, Favreau is really blending the practical and the CGI about as well as you can do it.

LP: Looking back on the collected Lucasfilm filmography now that 50 years have gone by, what do you think that body of work says about George Lucas as a person?

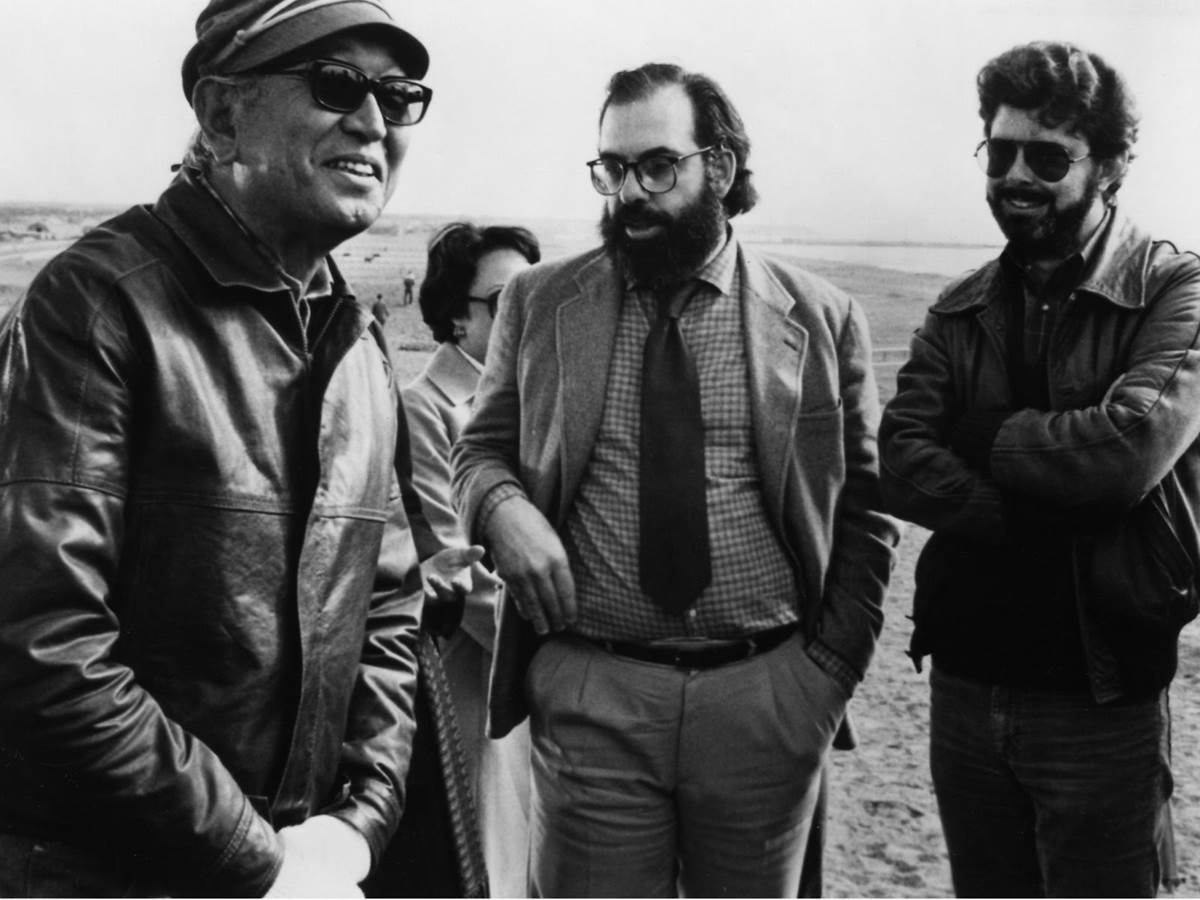

Jones: What I really admire about him as a producer– look at his stuff coming [out] through the '80s. First of all, I think it's astounding he was a secret producer on Body Heat. He was like, ‘I don't want my name on a dirty movie, but I believe in this project. This is the kind of movie I would love to make.’ I really admire Lucas's fearlessness in just making all sorts of different kinds of movies. Lucas loves film. He likes to watch movies and he likes making movies and he likes watching his friends make movies. I think a film like Mishima looks like Lucas's college films in a way. I think Lucas was very excited about backing that film, [and] backing [Akira] Kurosawa [on Kagemusha], bringing Kurosawa over here and getting some of his films produced and distributed. Part of it is helping his friends, but Lucas is not afraid to support another person's vision by getting involved in as much as he can.

Part of his idea is, he's the [executive] now, so he's going to try to give you the protection to keep the suits out of it. He does it in something like Return to Oz, which isn't necessarily his project. It's Walter Murch– his directorial debut, and Disney hates him and they're trying to bully him out, and Lucas steps in. He’s like, ‘How dare you get rid of [my friend]? You need to let this guy make the movie he wants to make.’ At that point in his career, Lucas picking up the phone and calling the CEO of Disney in the middle of the night was going to leave a mark. I really admire the courage it takes to put your name on a wide variety of products. Would Howard the Duck have really been the colossal dud and the laughing stock it is had Lucas's name not been on it? I mean, part of the relish that critics took in smearing that movie was like, ‘Oh, this is Lucas.’ His name's at the top of the poster. He's the easy target.

Had his name not been on that, you might have had people [saying], ‘This is a really interesting sort of culty kind of film here. There's something interesting going on here. There's some new ideas. They're not always executed well, but there's something new going on here.’ But the minute you slap Lucas's name on it, it's an easy target. So again, it really took courage to put his name above the title on some of these movies and really take the bullet. As I said earlier, that's what I really love and admire about him as well: when a movie like Howard the Duck bombs, [we get] no apologies from Lucas at all. He's like, ‘This is the movie we wanted to make.’ And you’ve really got to admire that.

The one that I really love is Tucker: [The Man and His Dream]. First of all, it's such a sweet movie. It's got a lot of heart, it's constantly interesting, the performances are fantastic. I know Coppola felt that Lucas went in there and took over and he made the movie. I disagree with that. I still think that movie looks like a Francis Ford Coppola movie. I'm glad Lucas talked him out of turning it into a musical as he initially talked about. So there are some places when Lucas went in there and tried to make sure Coppola wasn't indulging his worst storytelling mechanisms in that. But I think Tucker is a really sweet movie. The part of it that just tugs at my heartstrings is when people asked what Tucker was about and Lucas said, ‘It's about Francis,’ because it really is. I mean, this is somebody who's trying to make his dream and do it his way, and he's defying that. It's Lucas' story as well. I think that's why that film works– because that story is really important to both of those guys. I really think Tucker is the sleeper hit.

LP: What are your thoughts about Lucasfilm's future now that The Walt Disney Company owns it and it's being run by Kathleen Kennedy?

Jones: I think she's doing fine. Again, it's easy to be a scoffer. It's easy to be a cynic on this, but for everybody who's like, ‘The Last Jedi sucked,’ then they turn around [and] they're like, ‘But I love The Mandalorian.’ I mean, you win some, you lose some, I guess. I don't have any complaints about much of the output at all coming out of the new Lucasfilm over there. I think she's done a fine job and she's smart enough to find great creators and give them creative control and assign them projects and let them apply their vision to it. Something like The Mandalorian, and Rogue One, and probably hopefully something like The Book of Boba Fett, all these great projects all have a name attached to them. And she's smart enough to light the fuse and stand back on those, which I think is the way to go. I think that's part of what Lucas wanted out of the Disney deal.

Well, Lucas wanted some different things out of it– he still wanted to be in control of Star Wars. But I think one of the best things you can do when you've got your company parked at Disney is, you want the Disney machine there for publicity and streaming and things like that, but you still want your people there. Again, two of my subjects, both Jim Henson and George Lucas– one of them did sell their company to Disney, but Jim Henson in his lifetime was trying to sell his company to Disney. The Muppets eventually went there, but Jim was trying to move the entire company. I'm talking about Dark Crystal and Fraggle Rock and The Muppets. [He wanted to sell] everything to Disney because he understood that having the Disney machinery behind you really mattered. And I think what's important here is the lessons Disney learned in not successfully acquiring The Henson Company at first, and then once they did acquire [The Muppets], sort of blowing it.

I think they learned the lessons on how to do it there. And one of those lessons is, you acquire the company and you leave it in place. They didn't learn that lesson with Henson. They didn't acquire Jim Henson Associates; they were trying to blend Henson Associates into Disney. They got smart when it came to Lucasfilm and Marvel. They're like, ‘You maintain the semblance of an independent company, in a manner of speaking. You're still Marvel and you're still Lucasfilm.’ So you've got the advantages of having that Disney machine behind you while you still have a figurehead there. That's what's really smart, and again, that's where Disney blew it when they were working with The Henson Company in the '90s. That's a valuable lesson: you leave people in place who understand the company. In my opinion, they were smart to leave Kathleen Kennedy in place. I know people will differ over this, but I think they were really smart to leave her there.

She knew Lucas [and] she was involved in a lot of great movies before the acquisition of Lucasfilm, so I think she was a natural choice. She was continuity for Lucasfilm inside Disney. But she also knows an awful lot of really talented, great people who get her product– who get Star Wars, who understand it and want to work on it. She cultivates that, and if sometimes people think it works, other times it doesn't, but I don't think anybody would say, ‘Every Star Wars product that's come out of Disney under Kathleen Kennedy has been an abject failure.’ So when the people who call for her head are like, ‘Everything she's produced sucks,’ well, do you like The Mandalorian? You’ve got to grudgingly give her credit for something like that. That's my long roundabout way of saying I think she's done just fine.

LP: Since you did write a biography about the man, what do you think George Lucas is up to these days? We've got the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art that's still under construction in Los Angeles, but you have these quotes from him in the book where he keeps talking about going off and making these little films that nobody's going to want to see. Do you think he's doing that?

Jones: I don't know. I mean, I love [when] Steven Spielberg [says], "We're still waiting, George." I have a narrative going in my own head that Lucas has his own YouTube channel out there someplace that doesn't have his name on it. And he's dropping all these bizarre obscure short films, and everyone's going like, ‘What the heck is this stuff?’ And we'll find out in five years it's George Lucas dropping all these bizarre films on there. Lucas often says that his true love is what he always called the ‘tone poems,’ the stuff like his college films. I think it's fascinating– he always considered himself a documentary filmmaker, which when you go back and watch the original Star Wars kind of makes sense. It is interesting to watch the way Lucas has the camera find people, people wander into the shot. It is an interesting mentality, but I would like to think Lucas is trying to make those kinds of movies.

The other thing that keeps happening is we keep finding out he's had his hands all over The Mandalorian and other projects like that. So if they're still keeping the door open and letting him work behind the scenes and we're getting great product out, you get no complaints from me on this stuff. I mean, I'm not a Boba Fett fan and I'm psyched about The Book of Boba Fett because it looks like a mob film to me. I just think it looks fantastic, and I think maybe that's the remnants of [the live-action TV series] Star Wars: Underworld that Lucas was proposing at one point, so I wouldn't be surprised to find out his hands are going to be all over that as well. I think he's at the point where he is like, ‘Take my suggestion or don't. Whatever.’ He's having fun working behind the scenes. He doesn't have to be the one chasing the overhead on this anymore. He's still got Skywalker Ranch out there that he's happy to rent to people like the Disney Company to come in and do sound, and do special effects at ILM and so on.

I would like to think he's living his best life. People always ask me, ‘If you could ask George Lucas one question, what would it be?’ because I did not get [to interview] him for the book. And I think my question would be, ‘Are you finally happy?’ Mark Hamill always talked about [how Lucas] just looked absolutely miserable on set the whole time. I [would] ask him, ‘You sold the company, you ran the table, you did it all. You're involved in this thing that's going to outlive you and outlive your children and grandchildren, your great grandchildren. You've given us a piece of pop culture that will never go away. Are you happy?’ I would love to know the answer to that.

George Lucas: A Life is available now wherever books are sold. The full audio version of this interview will be available in the second-season finale of Laughing Place’s Star Wars podcast “Who’s the Bossk?”