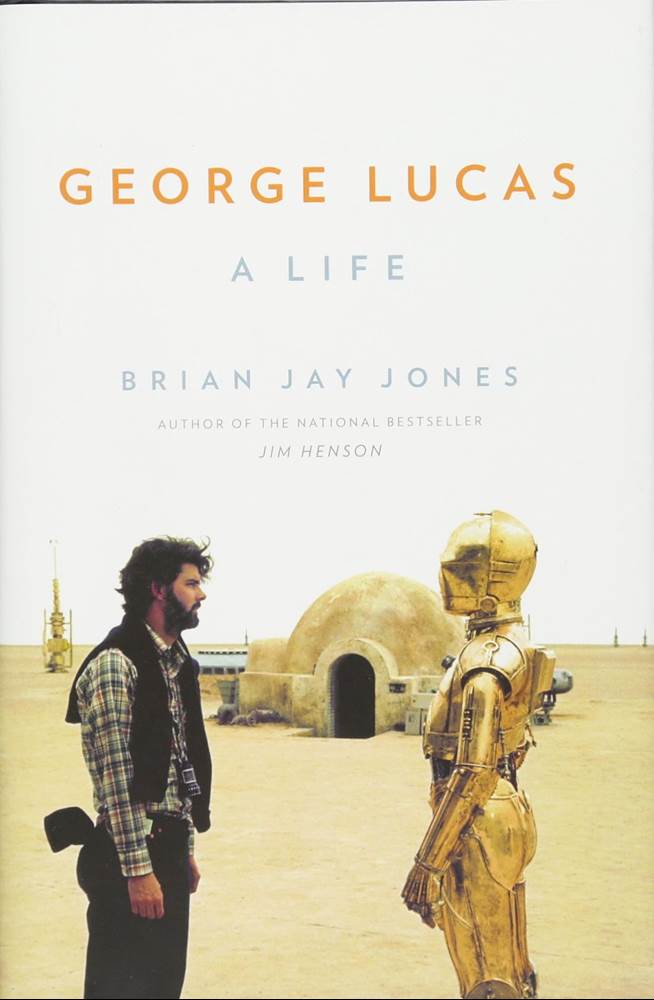

In December of 1971, George Lucas established Lucasfilm after his frustrations dealing with the Hollywood studio system while making his first feature film THX 1138. Now, in celebration of Lucasfilm’s 50th anniversary, I sat down for an extended chat with author Brian Jay Jones, whose 2016 biography George Lucas: A Life is arguably the current definitive (though officially unauthorized) version of the history behind the company and the man who created Star Wars.

In this first part of a two-part interview, Brian Jay Jones and I discuss George Lucas’s early life, the reasons and strategies behind the founding of Lucasfilm, his working relationship with Jim Henson, and the author’s own interests in the topics at hand.

Mike Celestino, Laughing Place: What was your history with George Lucas, Star Wars, and Lucasfilm in general before this book came along? Were you a big fan growing up?

Brian Jay Jones: Yeah. Because I wrote a book about Jim Henson, I used to always say, ‘I'm Sesame Street generation one,’ [but I’m also] Star Wars generation one, because I was nine when Star Wars came out. I was pretty much the target audience for Star Wars. I was raised on Star Wars and my brother, who's three years younger than I am, had pretty much every figure from the first movie [and] most of them from Empire. Then by the time [Return of the] Jedi came along we were a little older, but we were still eyeing the toy aisle with envy, because back in those days grown men– or at least teenagers– didn't buy toys like we do nowadays. So I'd always been with Lucas from day one, at least when it came to Star Wars.

My mom kept telling me all about American Graffiti, which I’d never heard of, and [I] finally caught that on HBO when I was about maybe 13 [or] 14. My parents always talked about the scene where they pulled the axle off the police car, so I couldn't wait to see that part. But getting back to Lucas, I was in fourth or fifth grade when Star Wars came out and I read everything I could on it. I was fascinated by it. I read Splinter of the Mind's Eye when that came out, and I couldn't wait for the teaser for Empire to show up in Dynamite magazine, My friends that I used to debate on the playground whether Vader was a man or a robot, not quite getting the point that he was a little bit of both. So I've been there since day one with Star Wars; it's part of my pop culture DNA. It's part of everybody's pop culture DNA, but I am from generation 1.0 of that.

LP: I'm guessing because you wrote the George Lucas book, you've kept up with the Star Wars franchise. Are you up-to-date with all that material?

Jones: Yeah, I've kept up with it my entire life. I'm part of the problem, because [I’m] one of those people who buys Star Wars in every format it's ever released [on] and has different copies of the soundtracks and everything. I was always keeping up with Star Wars and saw the [Special] Editions in the theater. I'm not as up-to-speed on the [Expanded] Universe. Even though I ran a comic book store for some time, I never read the Dark Horse comics, so EU I'm very [behind] on. I know the references, like when Ahsoka showed up in [The] Mandalorian I knew who that was, and I know who Mara Jade is. I know some of the big ticket items, but the EU [in general] I'm not quite up to speed on.

LP: Almost a decade ago George Lucas sold Lucasfilm to The Walt Disney Company. Is that around the time when you decided to start researching and writing this book?

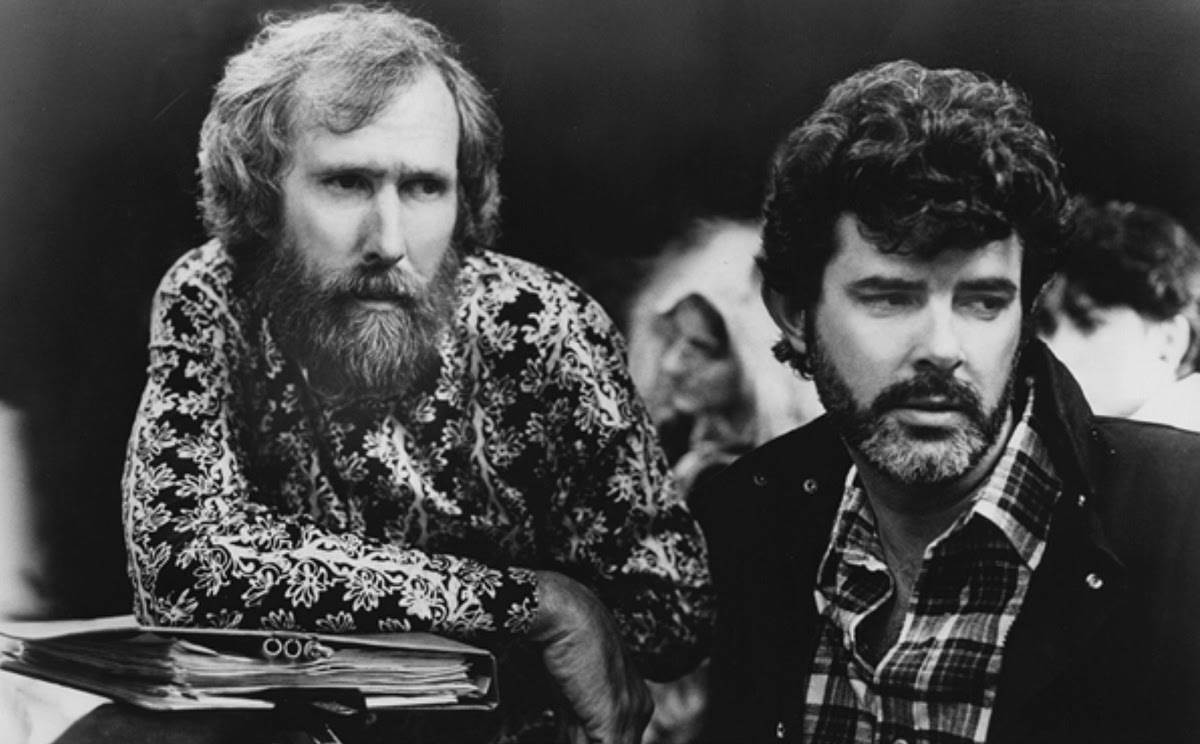

Jones: No, it wasn't because of that. I actually wanted to research and write this book because of Jim Henson. When I was writing the Jim Henson biography, as anyone who's a Lucas fan knows, and people who are Henson fans know this of Lucas, the two of them worked together on Labyrinth, Jim Henson's [1986] film. That's a period in Lucas's life where he stepped away from directing, and even from Star Wars, and is producing films by a lot of his friends. Henson is one of those people– not necessarily a friend, but a creative colleague of his– and they were across the street from each other at Elstree [Studios]. Jim was making [The] Muppet Show while Lucas was filming Star Wars, so they were in each other's circle.

When I was writing that chapter on Labyrinth, there's not many times as a biographer you get an opportunity to have both of your subjects in the same photo. There's that great photo of the two of them working together on Labyrinth and there's another one of them with [David] Bowie, but there's one of just the two of them. I actually have that photo in the book, and even though it's a publicity still, I had reached out to Lucasfilm and I was like, ‘Hey, I'm writing Jim Henson's biography and I want to put this picture in there.’ I didn't necessarily need permission, but I was like, ‘I'm going to put this in here, and if you’ve got any issues, let me know.’ And they were like, ‘Okay, that's great.’ Then after the book came out, my editor told me that Random House had received a note from George Lucas saying, ‘Jim Henson was a friend of mine, and the Jim Henson biography is beautiful. What [a] great tribute to that friend of mine.’

And I was like, ‘That is fantastic. He needs me to be his biographer.’ I was really interested in doing it because of that picture with [him] and Jim. So after I heard that, I wrote him a long email like, ‘I should be your biographer and you're getting ready to sell your company. Let's get you on the record, and let's talk about your life and career and your work,’ thinking he was dying to [have it] done. Not so much, actually. I did get a ‘no’ back, which people who are in the know told me ‘that's incredible’ because he usually never says anything. Actually, what I got was ‘not at this time,’ which I was like, ‘Ooh, maybe he’ll do it later.’ But I went ahead and did it anyway, because he's been speaking on the record since about 1964 so there was always plenty there to work with– which wasn't the case with Jim who never sat for interviews. I actually got into the book just because of his collaboration with Jim Henson, [which] really made me want to do that project next.

LP: What else do you think George Lucas and Jim Henson had in common?

Jones: What they both have in common… well, there's a number of things: both of them are very creatively restless. They always have one project that they're pitching, and another one that they're filming, and another one that's in post-production. There's always just constantly something going on; they're constantly in motion. And some pitches, some ideas don't go anywhere, and somehow they're mature enough to be like, "That's okay," and they move on to the next one. Sometimes they're not. Sometimes they really bird-dog something that they believe in, but both of them are really these creatively restless people. They're both really about absolute control over their product– Lucas more so than Jim Henson. For example, both of them maintained absolute control over merchandising, which for both of them was a brilliant decision.

Just as Lucasfilm was built on the backs of 3 3/4-inch [Star Wars] action figures, Henson Associates was built with Sesame Street marketing [and] merchandise. Jim made sure that he put his hands on everything and approved everything and would say, ‘I don't want this with my name on it.’ Lucas was very much that same way, too: [he] didn't want people getting junk [and] really took pride in the product they were putting out. They both have that as a similarity as well– that need to control. Now Lucas is much more controlling when it comes to his film work. What's interesting is both of them are also very collaborative, even as Lucas still has the need to control, but they're both really good at collaborating with people. Lucas tends to have that circle of friends that he keeps coming back to, and that to him is always enough. He enjoys collaborating with friends.

Jim Henson likes collaborating with friends, too, but he also really likes collaborating with creative people. And throughout his career, [he] pairs up with Brian Froud on Dark Crystal and Labyrinth, and brings in Bowie for that and asks Terry Jones to write the script because he's so impressed with Erik the Viking. Creativity turned Jim on more than anything else. So they both are attracted to cooperation, but in varying degrees. That's two of the big things, but that marketing thing is really something they have really strongly in common. I think after Jim passed, Lucas said, ‘We were both really very much alike: we're insistent on that creative control over our product.’ Now Lucas, as I said, is a little grumpier about it than Jim was, but they both really valued their work. They both had an absolute vision of what the final product would look like that really drove everything. And sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn't.

But what I love about both of them is, you take something like Howard the Duck, a spectacular dud, and Lucas, when he is asked about it, [gives] no apologies. He's like, ‘We made the movie I wanted to make." And Jim Henson, with Labyrinth he's like, ‘That's the way I wanted that movie to look.’ And with Labyrinth Jim Henson's right at the wrong time. Howard the Duck… I don't know that Lucas is ever right with Howard the Duck, but it’s a fun movie.

LP: A big chunk of the early part of George Lucas: A Life is about him growing up in Modesto, California. What was it about Modesto and his family life that turned George Lucas into George Lucas?

Jones: As a reader of biographies, especially when I was much younger, I often got impatient when you get into the first chapter and it's all about family trees, and it's all about the hometown they live in. But for Lucas, you have to start there. Modesto matters in Lucas's story, and his family– mainly his father– really matters in his story. Modesto is [in] Northern California, but for a Northern California city, it's surprisingly sun burnt. It's remote [and] lovely up there. When you think of Northern California, Modesto's not the town that comes to mind. It's an isolated place… not that big but big enough, and Lucas's father was a very successful businessman. He ran his stationary store in Modesto and [during George’s] entire childhood and teenage years, Lucas's father assumed that he was going to hand the family business off to George. And George had no interest in running that family business.

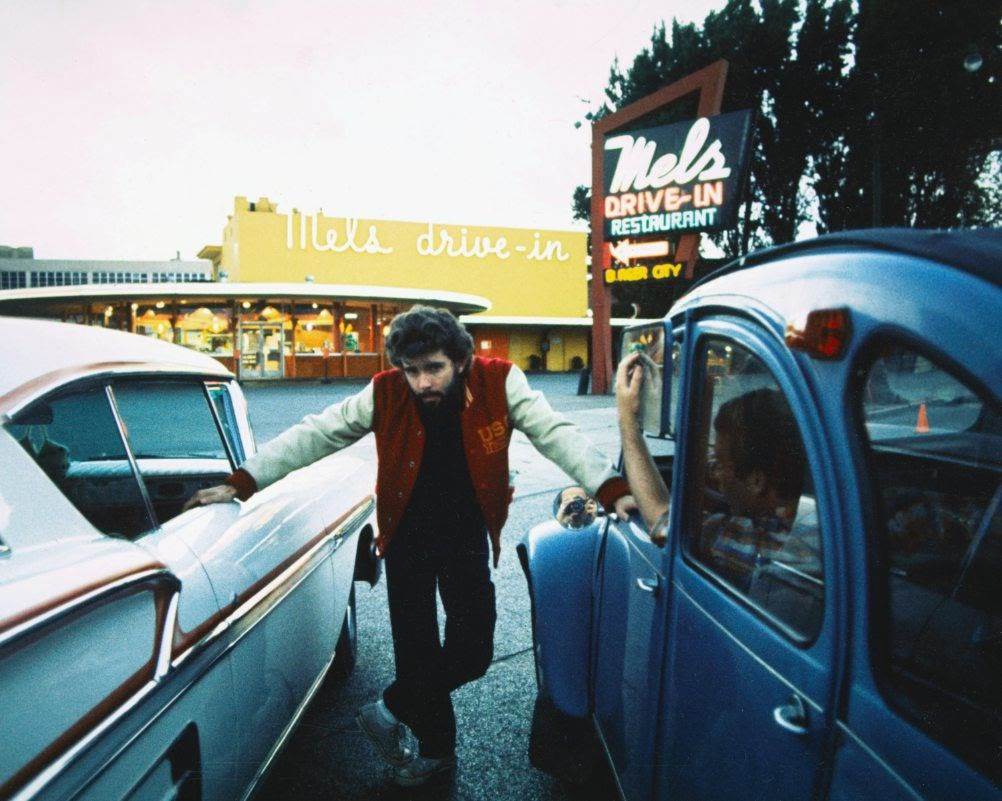

George was a dreamer: very interested in comic books. What I loved about Lucas with comics was his comics were so dorky. I mean, who's he going to read? If you're talking about George Lucas, you're like, ‘Oh, he had to be reading Adam Strange or outer space stories.’ A little bit, but his favorite comic book character was Tommy Tomorrow of the Planeteers, who's like an intergalactic policeman– a really odd one. [He also] loves the Uncle Scrooge stories of Carl Barks, which really comes through in his later work. But Lucas more than anything is just a gearhead. He's one of these guys that is really intuitively great at fixing things, and loves cars, and loves to drive fast. His father finally got him this little teeny foreign car with this little teeny engine in it– Lucas called it a sewing machine engine. His father was like, ‘This is the car you're going to drive, because otherwise you're going to kill yourself in it.’

And of course Lucas, like the Millennium Falcon, takes it apart, puts it back together with a lot of special modifications he makes himself. And [he] ends up being a really great driver, partly because he's small. He doesn't weigh that much– he probably weighed 100 pounds soaking wet. But that's Lucas as a teenager. If you’ve seen American Graffiti, that's kind of Lucas's high school years. Lucas is a combination of those four characters– he's a little bit more the dork than anything else, but he was one of these guys that goes out every night if he can, and goes cruising up and down the streets in Modesto all night, out late neglecting his schoolwork. So Lucas is really of Modesto. He doesn't necessarily reflect Modesto, but he really loved that town [and] the cruising scene. All he thought he was ever going to get out of that was being an auto mechanic or maybe a racecar driver, something like that. [He] wasn't really all that interested in school.

LP: Is there a line connected between tech of car culture and the tech of filmmaking for Lucas?

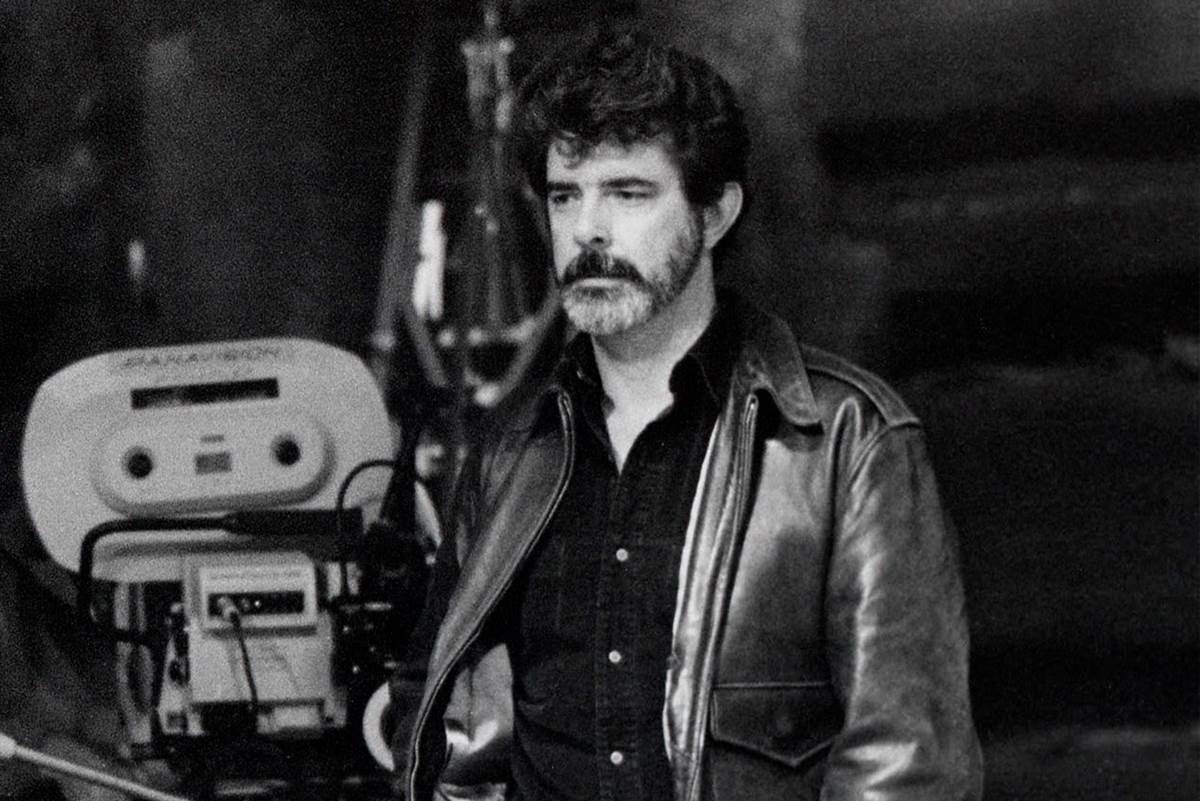

Jones: I think there absolutely is, but for a different reason. When Lucas finally defies his father and says, ‘I don't want to run the family business. I'm going to go to college,’ initially he wants to be a photographer or some kind of artist, but he knows his father won't pay for that. So he says he's going to be a cinematographer, which he thought sounded sufficiently science-y enough that his father would let him get away with it. So he goes down to University of Southern California and enrolls in the film program. What's interesting about Lucas is compared with somebody like Steven Spielberg, Spielberg had film in his DNA, in a way. Spielberg's the one who at age eight is filming Super-8 reels of his trains crashing together, running in slow motion. Lucas didn't do that, Lucas doesn't necessarily have any interest in filmmaking.

He somewhat liked film and liked Saturday morning serials and things like that, but didn't necessarily have any aspirations to be a filmmaker. Lucas was very into anthropology and things like that, but he gets down in the cinematography program and what he discovers is that he's a fantastic film editor. And I think one of the reasons that he was a great editor– which makes him eventually a great storyteller on film– is that [with] the original equipment they would use to cut and edit film, you would thread the film in and you would move the film forward or backwards using pedals on the floor, [using your] left and right foot. And there was a handbrake to stop the film that you would pull with your right hand, and there was a visor– almost like a windscreen to look through– as you're doing it. It was like sitting behind the wheel of a car, which is what Lucas had done for the last five years of his life.

And Lucas– the gearhead– because it was so second nature to him, became one with that machine. Lucas is very Vader-like, in that man and machine are one. When you put Lucas behind editing equipment, he doesn't have to think about it. He can concentrate on the product itself because he's not bogged down in the mechanics of making the editing machine work. He just had a knack for that, again, from working on cars and driving cars. The equipment is completely out of his head; he can focus on editing [and] on the product itself, and he turned out to be just a fantastic editor in that regard. And that's where he becomes the boy wonder down at USC. But early on, he's doing what George Lucas would do the rest of his career– in that, if you give him a rule he's going to break it.

One of his first projects is in an animation class, and they said, ‘We're going to give you a little bit of film here and we want you to make a really short animated film that shows that you can move the camera left and right, and make it go up and down’– very rudimentary stuff: no sound, no color, nothing like that. Well, Lucas of course puts sound in his, and he does this series of quick cuts where it's like pictures from magazines. [The short film is] called “Look at Life,” and you can find this on YouTube if you want to watch it. It's pictures from magazines that he's panning across to make them look like they're moving, and this percussive drumbeat of a score behind it– really fantastic stuff. I think Walter Murch– who's an old friend of his who's a fantastic sound engineer– later said they got done watching that and someone said, ‘Oh, we’ve got a live one here.’ So from moment one, Lucas was wowing them, first by breaking the rules. But second of all, [he had] a fantastic knack for editing because the machinery is completely out of his head.

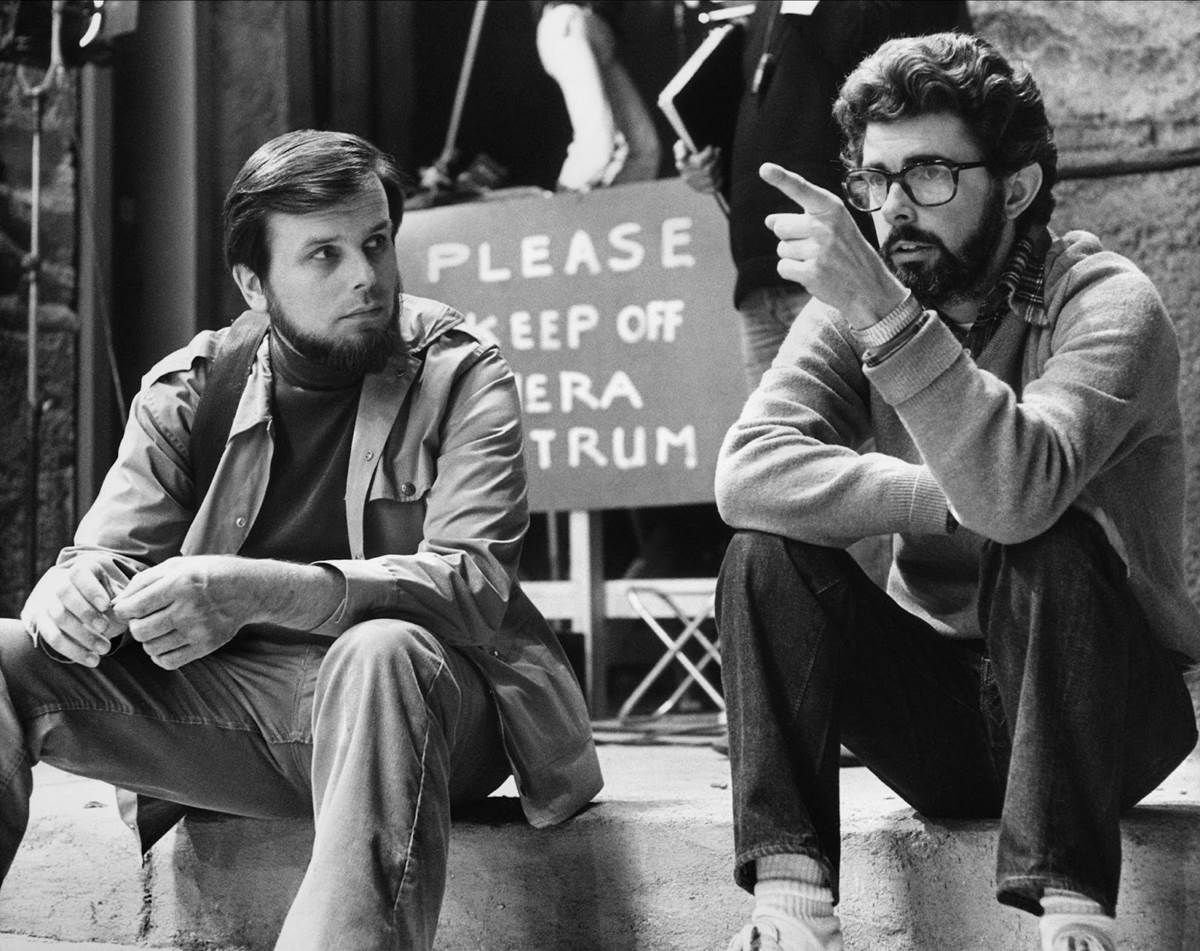

LP: There’s a quote in your book from a film critic who said something to the effect of Lucas’s output being better when he's working with a collaborator who will challenge him, rather than a yes-man who will simply adhere to his every decision. Is this something that you personally agree with?

Jones: Yes. Part of what made Lucas work was pushback and somebody like [Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back producer] Gary Kurtz coming in and saying, ‘That's not going to work’ or ‘This idea is only half-baked or half-formed; we are going to try something different.’ So they were constantly telling Lucas ‘no,’ and part of it is he's [also] bickering with the studio who won't give him any money for Star Wars and even for Empire. But by the time he gets to Jedi, he's running the table. There aren't many people [who are] going to tell him ‘no.’ He makes poor Rick McCallum miserable by the time he gets into the prequels. I mean, he's financing everything, [so] he can just do whatever the heck he wants, and that lets him indulge his worst instincts and his worst storytelling instincts, in a way. Whereas somebody like Kurtz actually quits over storytelling.

When Lucas was drafting the original version of Return of the Jedi, he essentially wanted to do another Death Star– and it’s what he does. And Kurtz was like, ‘I don't want to do this again.’ One of the early drafts had something about Luke becoming the last of the Jedi and [he] goes off to look for other Jedi, walks off into the sunset, and Leia is in charge of the Rebellion now, so it's almost got this bittersweet ending to it. He was really all for that; that was where Gary Kurtz wanted to go. He didn't want to do the same old same old again, and when Lucas said, ‘No, we're doing another Death Star,’ that was when Kurtz said, ‘I'm out.’ I think Kurtz still has a credit on Jedi, but he gave up early because he pushed back on story and Lucas was at the point now where [he could] say, ‘Well, there's the door.’

In A New Hope, there's that really interesting line where Tarkin says, ‘We've dissolved the Senate; we've returned power to the regional governors.’ It's a complete throwaway line, and it's so interesting. It's like this completely discarded backstory. [The] first time I saw the movie, I didn't pay attention [to it], but when I listened to that later and heard that line, I was like, ‘Oh my God, the regional governors– that sounds so super interesting. I would love to know more about the politics of Star Wars.’ Well not so much, because once Lucas starts giving us the politics [of] Star Wars in Episode I, we're talking about taxation rates and trade. That's Lucas indulging his love of backstory, and I think had he had somebody who was a little bit more of a ‘no’ person who pushed back a little bit, they might have gotten him to pare some of that down.

Or had he even brought in [American Graffiti screenwriters Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck] like he did with Star Wars, and said, ‘Make this thing funny,’ they might have gone through and said, ‘This scene here isn't going to work, and this is slowing you down.’ Maybe a collaboration like that would've beat that script [into] a little bit better shape. Because when [Lucas was] writing Star Wars, I mean, he's got the guts to hand that incomprehensible script off to friends who fix it for him. By the time we get to Episode I, he's just not doing that anymore. Lucas has earned the right to do that by the time [The] Phantom Menace comes out, but it really does let him indulge himself a little bit too much, I think.

LP: A big theme in the first half of his career where Lucas wants to be a filmmaker, is that he hates dealing with the executives who are running the studios. So when he goes on and creates Lucasfilm, in what ways does he do that to avoid the same pitfalls that he disliked in the Hollywood studio system?

Jones: First of all, that comes out of Lucas as a teenager telling his father, ‘No way I'm going to run the family business. And I'm going to come back and be a millionaire before I'm 30.’ The reason Lucas despised the [executives] and despised what we'll call the Hollywood machine is because they were in the artist's way. And that had happened to him constantly. It happened to him in THX 1138 when he had the first version of the film and the studio watches it and they're like, ‘You got to cut four minutes out of this.’ [It] almost seems like a random number, except when he gets to American Graffiti, they say, ‘Cut four minutes out of this.’ Lucas always felt like they were just saying that because they wanted to have something to say. They didn't know what filmmaking was; they were just trying to impose on the artist. Lucas really resented that they were in the way.

When he and Francis Ford Coppola got together with a couple of other filmmakers to form American Zoetrope in the late '60s, that was the first draft of Lucasfilm. [It was] this place where the radicals and the hippies, they called it, got together to make the movies they wanted to make. I compared that to The Beatles and Apple Records. The Beatles were like, ‘We're going to have a label where you can come and do whatever you want.’ And then it falls apart because nobody's looking after the business end of it, which is what happened to Coppola along with Zoetrope. Lucas was part of the problem, because THX came out and tanked and took Zoetrope along with it. But nobody was really minding the store. Lucas was determined not to make that same mistake when it's his own company. But Lucasfilm and Skywalker Ranch really come out of– not just that desire to get the suits out of the creative person's way– but to run the table.

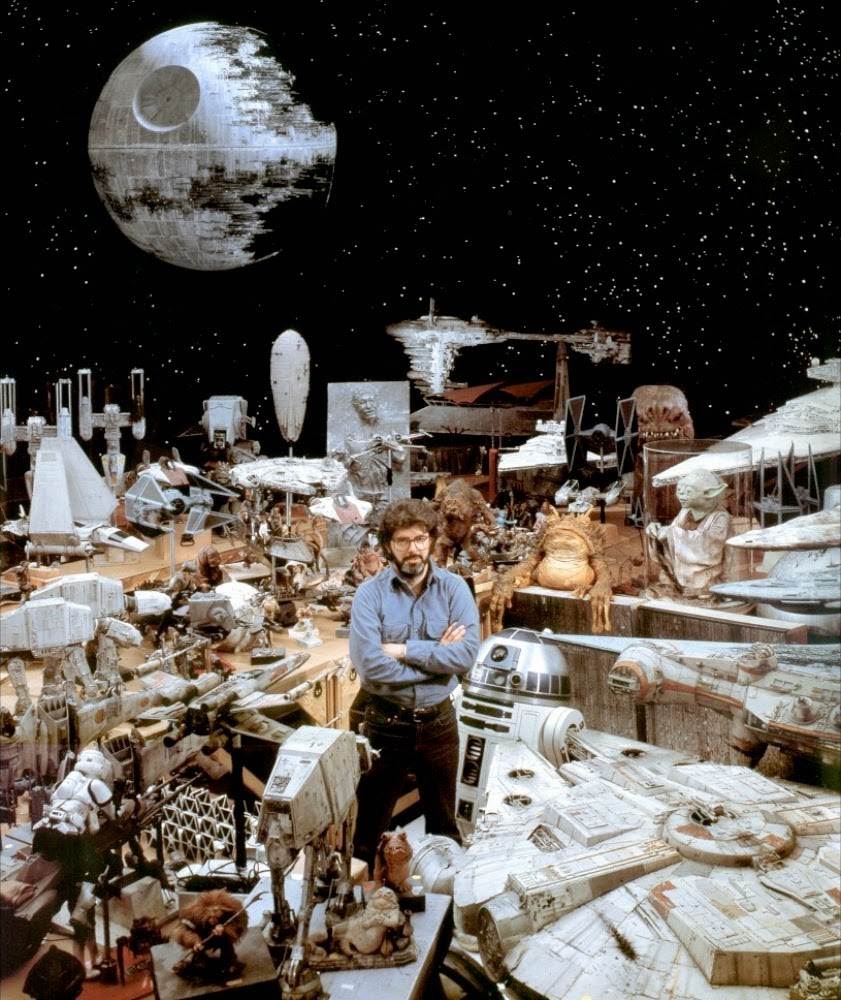

What I thought was so fascinating about him is how charmingly reckless Lucas can be at points, because he has with American Graffiti the most profitable independent film in history at that time. When you compare how much went into it versus how much it made, the ratio was gigantic. Lucas. who's trying to develop Star Wars, takes all of his profits from that and pours it right back into the development of that film, to the point where his wife Marcia was taking her day job in editing for Martin Scorsese, of all people. She's keeping the lights on while he's spending all of their money, and it [cost] millions developing Star Wars. But part of what he does while he's doing that is he says, ‘I need great special effects.’ And every studio goes, ‘Sorry, we closed up shop a long time ago on that.’ So Lucas says, ‘Okay, fine. You don't have it? I build it. I own it,” and builds [Industrial Light & Magic].

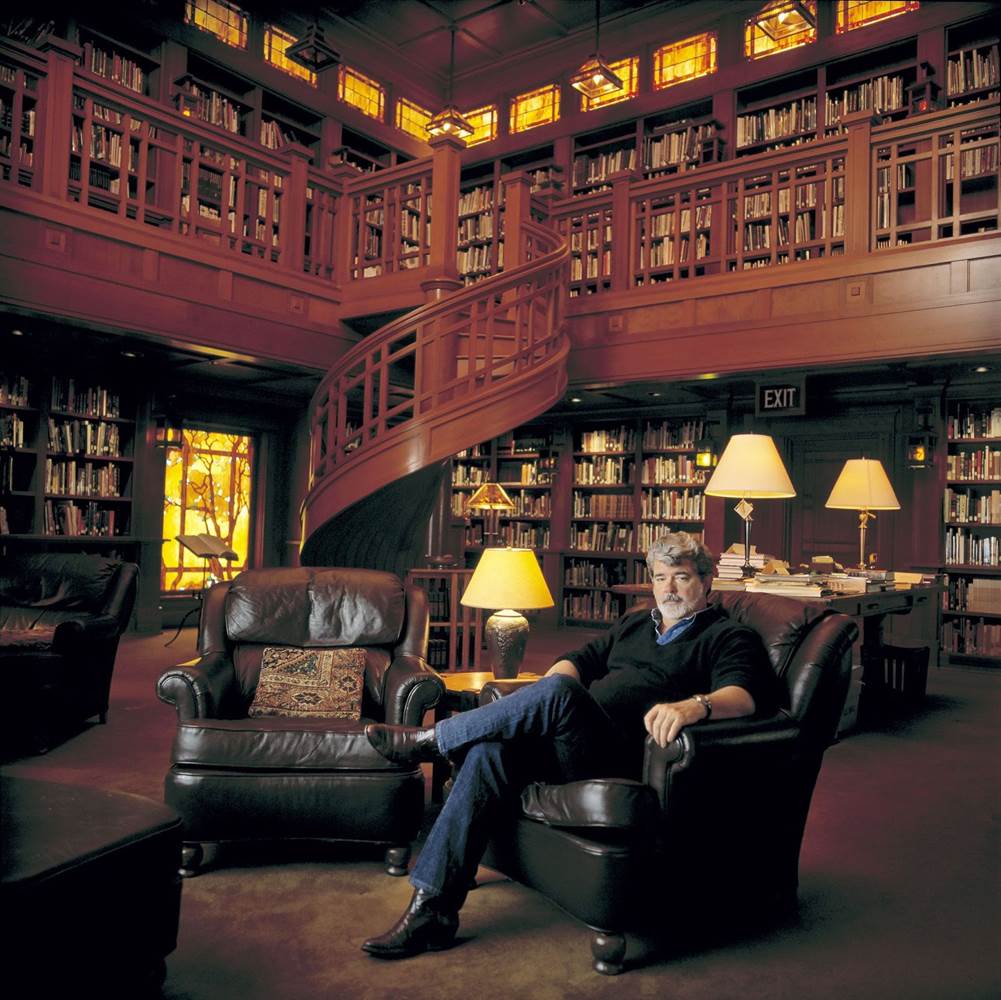

Now Lucas builds ILM, owns ILM. So when he starts putting together Lucasfilm and Skywalker Ranch, first of all he puts it as far from Hollywood as he can. He puts it in Northern California, back home where it's much more comfortable. They're in Northern California, and he parks ILM there. There's no studio, you can come out there as a filmmaker and use those facilities. He really liked the guerrilla filmmaking that had gone on [with] American Graffiti, and they even did some of that even at Zoetrope. You get in a car with a camera and you go and film something. Coppola did that with The Rainmaker, and Lucas loved that. So they weren't a studio in that sense, but they were a film facility where anybody who was an artist could go and wield their craft without interference from the studio, come in and rent the space and edit your film or use your special effects.

As time goes on, Lucas keeps adding more and more to Skywalker and to Lucasfilm in that urge to run the table, in that urge to have no piece of the project that The Man is going to own. The one element that I find absolutely fascinating, because it is the part of the filmmaking process which by rights Lucas should have no say over, [is] THX sound. Lucas used to watch his own films in his video room at Skywalker Ranch, and then he would go watch them in a movie theater and he said, ‘My films sound awful in the theater.’ And his technician said, ‘Well, that's because when you're here, you're watching them with our sound system setup, and our sound system setup is awesome.’ And Lucas said, ‘Well, every movie theater should have awesome sound in it, then.’ And he develops THX sound.

I always thought growing up [that] THX was the equipment , [but] what THX initially was was a series of specifications that he would sell to movie theaters and say, ‘If you want your movies to sound great, [these are] the specifications you need to follow. This is how fast your film needs to be run, and this is the lights in the room, and this is where the speakers go and how loud they all are.’ He's dictating to the theaters how their sound system and even how their [auditoriums] themselves should be set up. Who gets to do that? George Lucas gets to do that, because what he says is, ‘Oh by the way, I've got a movie called Return of the Jedi here, that's going to sound awesome with the right sound system. So he is using his powers for good in that sense, waving Star Wars around as a hammer.

That part is so fascinating to me because it was just the fact that Lucas has the audacity to go out to all these small theaters and say, ‘Please refurb your theater to meet my specifications because I want my films to sound amazing.’ Now, it turns out everybody else's films sound amazing when they're mixed and shown in THX, but only Lucas could have gotten away with that. That to me is incredible. In fact, let me give you one more example of Lucas using his powers for good. He does it again with digital filmmaking. By the time we get around to Attack of the Clones, Lucas is in love with digital filmmaking. Lucas really did forge the future with that. The reason we have great CGI and great digital filmmaking is because Lucas was fascinated with that tech, and one of the reasons Lucas was fascinated with that tech is because it let him control the product absolutely.

You didn't like the color of the drapes in the background? Fine, you change them in post. You don't like the way an actor sounded? Great, you just redub them, and maybe you can even make his lips look different when you go back and redub it. Digital filmmaking was really Lucas's baby, and to this day he even says it's the thing he's most proud of. But at the time that Attack of the Clones comes out, Lucas is saying, ‘Theaters need to be showing their films digitally so they're not hauling around these big film cans. Theaters need to retrofit themselves to show digital films.’ Once again, who does that? Lucas does, because he walks in and says, ‘If you want to show an awesome movie like Star Wars, you should fit your [theaters] to show films digitally.’ Again, [he’s] pushing everybody along that he thinks are in the way of his vision, but it actually ends up being the tech we all deserve, in a way. Lucas does this constantly. That's what I find so fascinating about him: he's running the table in places he absolutely should have no control over.

Part 2 of this interview will appear later this week on LaughingPlace.com, and the audio version will be available in the second season finale of LP’s Star Wars podcast “Who’s the Bossk?” George Lucas: A Life by Brian Jay Jones is available now wherever books are sold.